Mechanical reverie.

The engineer’s flower.

Sketches, wood carvings, written records and surviving artefacts offer insights into the development of mechanical constructions. Pumps have been used to channel water for millennia. Weather vanes help us gauge the weather. Architects and engineers designed lighthouses and observatories to explore ideas and territories. Scientists perfected telescopes, rotating globes and astronomical clocks. Civilisation brought us the Tower of the Winds in Athens.

Text: Elise and Martin Feiersinger

Image credits: The Various Ingenious Machines of Agostino Ramelli, Fondazione Villa Il Girasole®

In the Mannerist period, machines took on surreal forms: robot-like figures interacted in a grotto, artificial birds twittered on a vase fitted with pipes. The animation was set in motion through the turn of a crank or by air pumped through a pipe. The spread of copperplate engraving made the reproduction of elaborate drawings easier. In Agostino Ramelli’s depiction of a study, published in 1588, a scholar in formal clothing sits at an apparatus – a book carousel. Lost in his thoughts, he also seems lost in time.

Text: Elise and Martin Feiersinger

Image credits: The Various Ingenious Machines of Agostino Ramelli, Fondazione Villa Il Girasole®

In the Mannerist period, machines took on surreal forms: robot-like figures interacted in a grotto, artificial birds twittered on a vase fitted with pipes. The animation was set in motion through the turn of a crank or by air pumped through a pipe. The spread of copperplate engraving made the reproduction of elaborate drawings easier. In Agostino Ramelli’s depiction of a study, published in 1588, a scholar in formal clothing sits at an apparatus – a book carousel. Lost in his thoughts, he also seems lost in time.

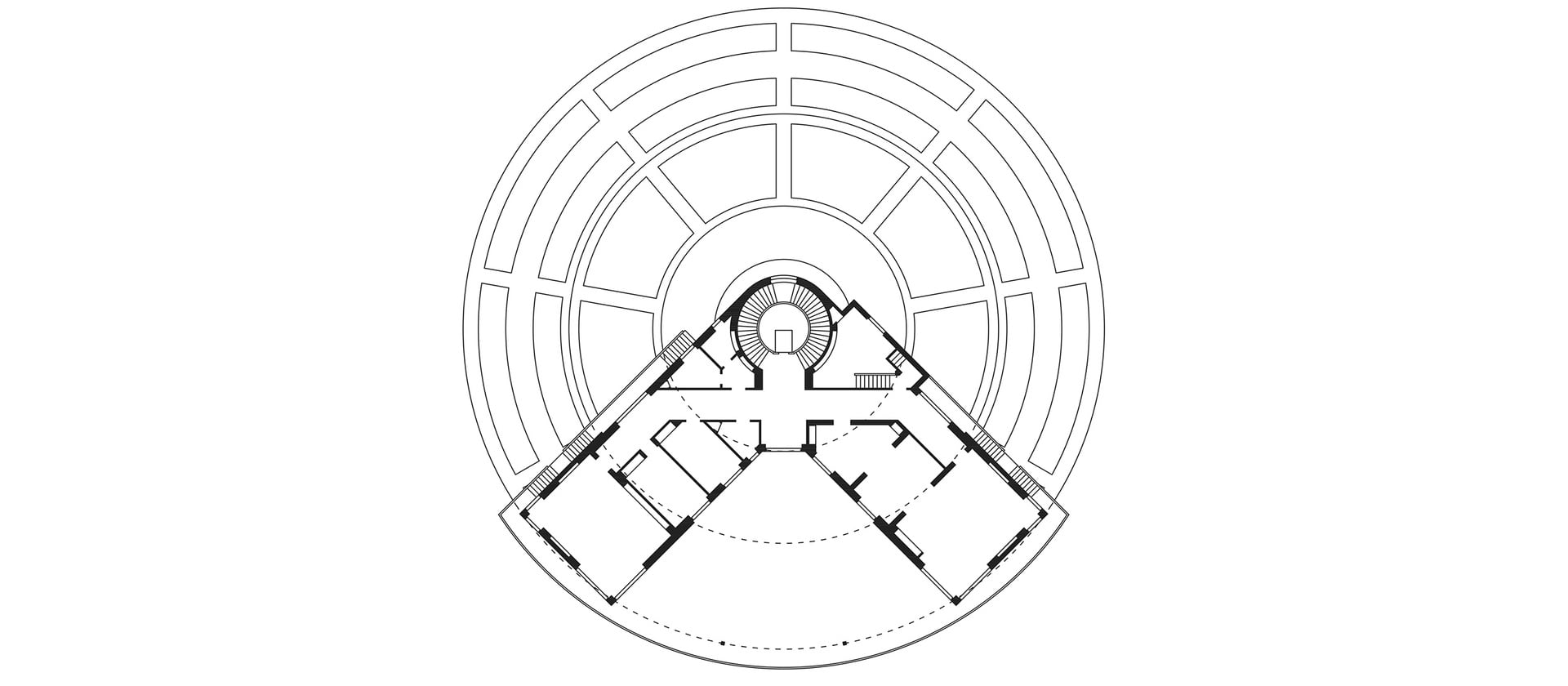

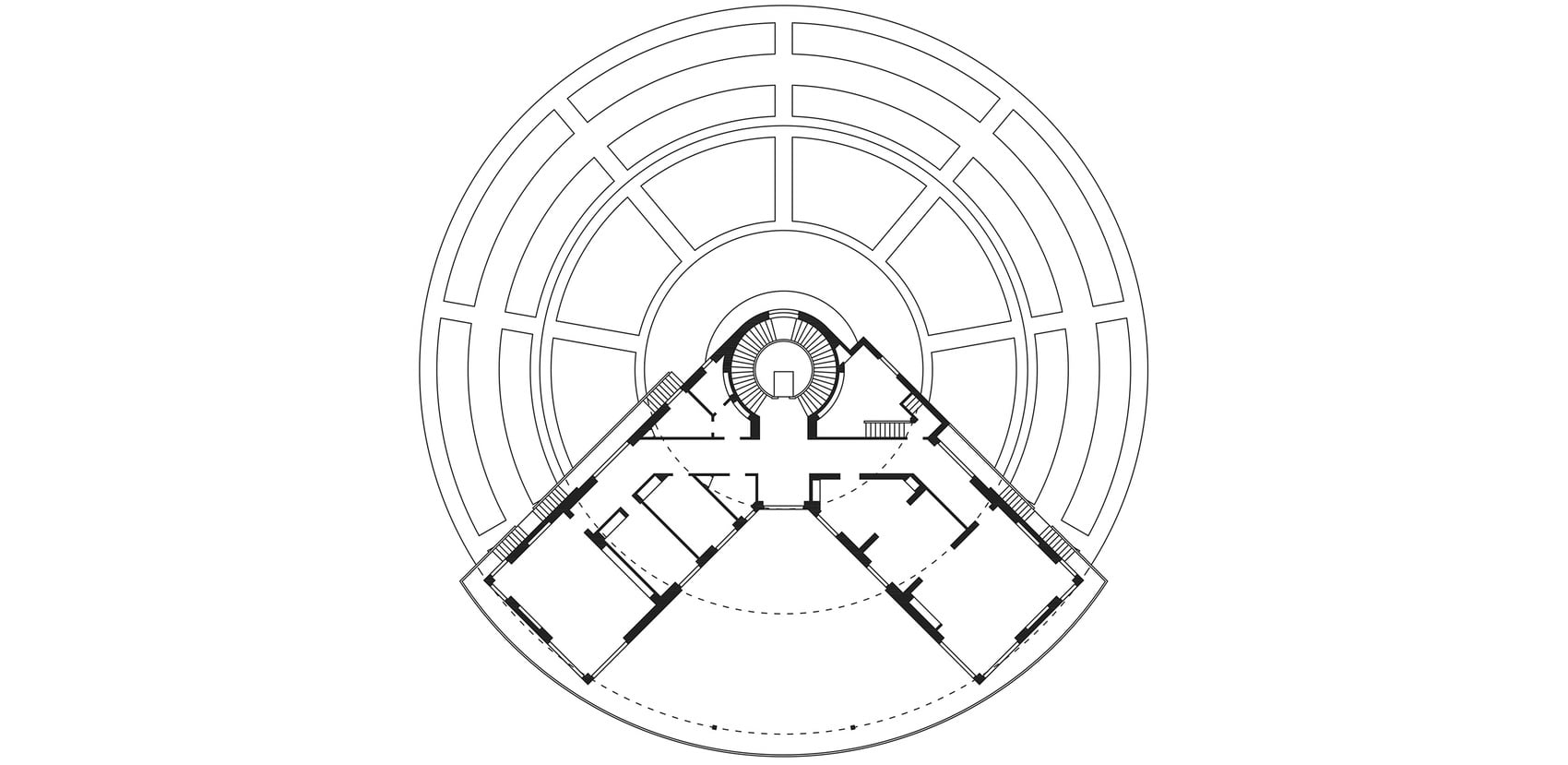

Floor plan of the rotating storeys with the terrace occupying three quarters of a circle. The lawn sections and the even divisions between the tracks map the scale of the rotary movement.

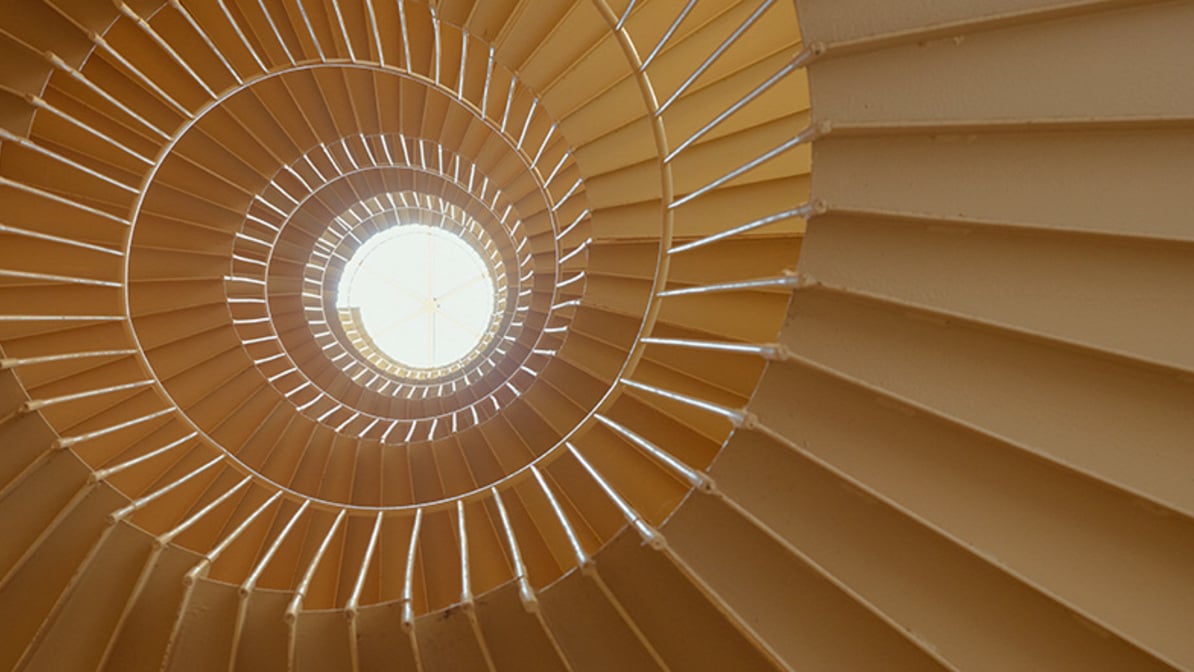

Around 350 years later, in Genoa, engines came into play. The engineer Angelo Invernizzi spent his days amid the bustle of the busy port. His vision of a holiday home in the idyllic landscape of his childhood would push the technology of his time to its limits. Invernizzi experimented fearlessly with the tools of his trade. The house he built in Marcellise rotates on a monumental round plinth – supported on one side by a colonnade, on the other by the ground. The wide terraces recall the decks of a ship. The motion is so slow that it is barely perceptible to the residents.

It is difficult to capture the significance of this structure in a few words. It raises so many questions: is the Villa Girasole just an enigmatic flight of fantasy? Or is it an allegory that reminds us how knowledge is passed from generation to generation? Or does it symbolise the eternal oscillation of the pendulum – with each generation trying to achieve the ostensibly impossible anew?

Elise and Martin Feiersinger

In their projects, these two Vienna-based architects engage with transitions and disruptions in architectural development, with urban planning and existing buildings, with issues of residential living and the everyday utility of ordinary objects.

It is difficult to capture the significance of this structure in a few words. It raises so many questions: is the Villa Girasole just an enigmatic flight of fantasy? Or is it an allegory that reminds us how knowledge is passed from generation to generation? Or does it symbolise the eternal oscillation of the pendulum – with each generation trying to achieve the ostensibly impossible anew?

Elise and Martin Feiersinger

In their projects, these two Vienna-based architects engage with transitions and disruptions in architectural development, with urban planning and existing buildings, with issues of residential living and the everyday utility of ordinary objects.

Agostino Ramelli’s book wheel, 1588. The mechanism of the reading machine is constructed so that the incline of the individual lecterns remains constant as it turns.

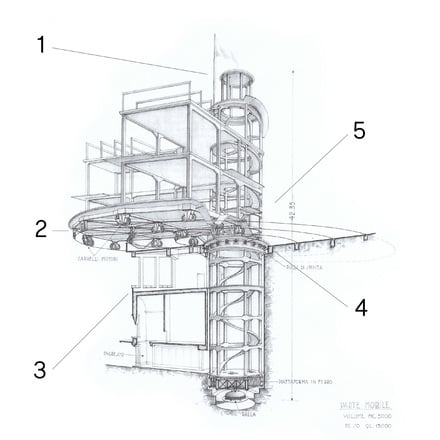

Cross section of Invernizzi’s rotating Villa Girasole

1: Outlook

The vertical thrust culminates in the cupola; to reach it you have to leave the backbone of the structure. The highest set of stairs deviates from the template, protruding cantilevered from the framework. The filigree railing structures on the terrace frame the view of the landscape.

2: Engines and wheels

The reinforced concrete skeleton rotates on its base on 15 pairs of one-metre-high wheels driven by two engines.

3: Plinth

The plinth rears out of the landscape. The route through the imposing entrance hall, which is at the lowest point of the plinth, leads to a spiral staircase that rises to a height of around 40 metres. Three concentric tracks are carved into the grassy top of the plinth. A by-product of the architectural concept, the semicircular loggia embedded in the plinth emerges as the most impressive of all the spaces.

4: Forces

The ring in the middle of the spine absorbs the horizontal forces, so it has a larger cross section than the other elements of the rotating structure. The vertical forces are conducted to the pivot at the other end of the shaft.

5: Rotating skeleton

The entire slender skeleton is made of reinforced concrete – consisting of a central cylindrical backbone with two wings attached – which can be set in motion at the touch of a button.

The vertical thrust culminates in the cupola; to reach it you have to leave the backbone of the structure. The highest set of stairs deviates from the template, protruding cantilevered from the framework. The filigree railing structures on the terrace frame the view of the landscape.

2: Engines and wheels

The reinforced concrete skeleton rotates on its base on 15 pairs of one-metre-high wheels driven by two engines.

3: Plinth

The plinth rears out of the landscape. The route through the imposing entrance hall, which is at the lowest point of the plinth, leads to a spiral staircase that rises to a height of around 40 metres. Three concentric tracks are carved into the grassy top of the plinth. A by-product of the architectural concept, the semicircular loggia embedded in the plinth emerges as the most impressive of all the spaces.

4: Forces

The ring in the middle of the spine absorbs the horizontal forces, so it has a larger cross section than the other elements of the rotating structure. The vertical forces are conducted to the pivot at the other end of the shaft.

5: Rotating skeleton

The entire slender skeleton is made of reinforced concrete – consisting of a central cylindrical backbone with two wings attached – which can be set in motion at the touch of a button.

Reframe Sunshine

Mehr Interessantes zum Thema gibt’s hier.