Follow the sun.

Villa Girasole.

When you visit an architectural work after studying it intensively, preconception collides with reality. The scale, the context, the spatial and light qualities that photos often fail to convey can either surprise or disappoint. Architecture that seems banal in images often has an unexpected presence in real life, while expressive structures can be polarising. We travelled to Villa Girasole with no major preconceptions. We knew the work, but only superficially, and deliberately decided not to research too much before the trip.

Text: Aitor Fuentes Mendizabal & Igor Urdampilleta

Photos: Marta Tonelli

Image credits: Enrico Cano

Outside Verona, Angelo Invernizzi’s Villa Girasole rises at the end of a classic avenue of cypresses that winds up from the valley. Surrounded by vineyards and scattered farmhouses, the structure combines a futuristic vision with the aesthetic of an Italian manor house.

There is a carefully sequenced dramaturgy to the journey here: first you pass the simple caretaker’s house, then the winding path gradually reveals the silhouette of the villa. But before it is completely revealed, a pool with a concrete slide shaped like an elephant invites you to stop and pause. Then the house is revealed in all its glory: a building that rests on a monumental cylindrical drum, a volume that corresponds with that of the house.

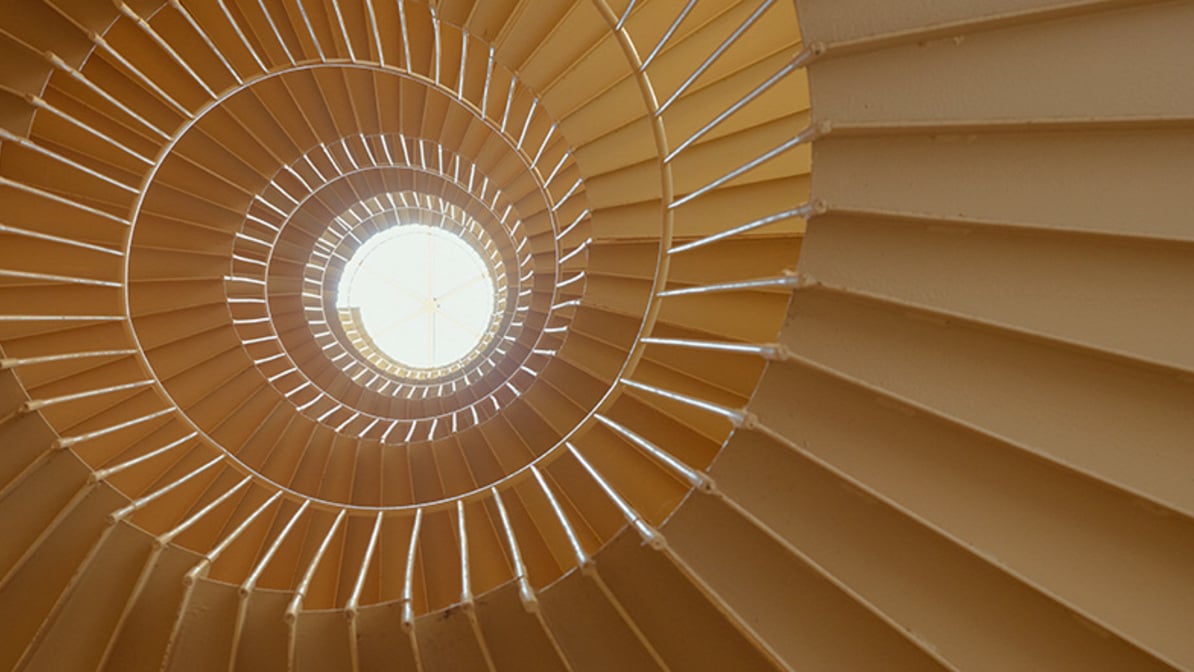

The cylinder is like another plot within the plot, a raised stage for the actual architectural experiment in which Invernizzi’s technical masterwork becomes tangible: a 42-metre-high spiral staircase with integrated elevator, around which the whole house revolves – architecture in motion, anchored in its own rotation principle.

Villa Girasole, built between 1929 and 1935, served as a summer house for the maritime engineer and entrepreneur Angelo Invernizzi, his wife Lina who suffered from tuberculosis and their equally sick son – architecture designed to revolve around light and healing, not just mechanically but conceptually as well.

In the 1920s, medicine started focusing more on the sun, especially in the treatment of tuberculosis. Architecture, particularly hospital buildings, transformed from mere lodgings for patients to therapeutic instruments that were designed to actively aid recovery through thoughtful orientation and ventilation. One prominent example is Alvar Aalto’s 1929 design for the Paimio sanatorium in Finland, which influenced numerous hospital buildings of the time.

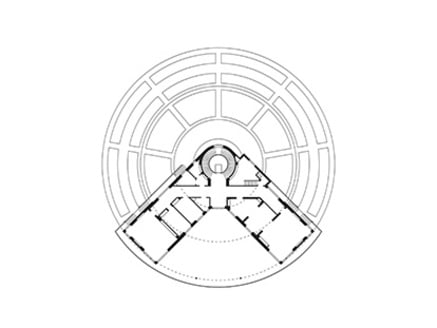

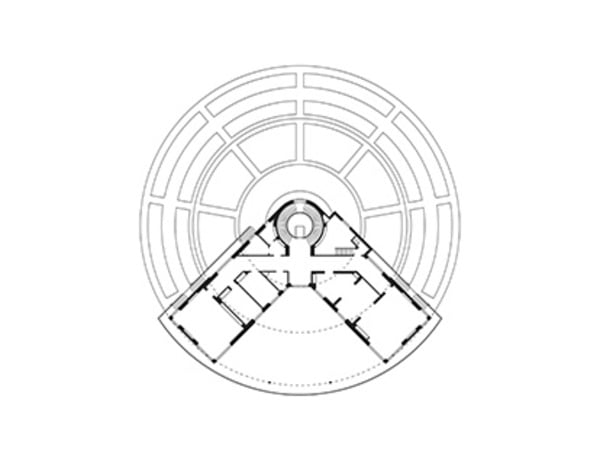

In Italy, this medical and architectonic transformation allied with Futurism as well as European rationalism – fruitful terrain for architectural experiments. It was in this context that Angelo Invernizzi made the bold decision to build a revolving house. Instead of a simple pavilion like the ones designed by French doctor Jean Saidman – including the revolving solarium erected in Aix-les-Bains in 1920 – he collaborated with architect Ettore Fagiuoli to design a multi-storey, L-shaped house. It rests on a cylindrical plinth which had to be partially embedded due to the sloping plot. This base provided the foundation for an architecture that literally followed the sun.

The dynamism of Villa Girasole is already apparent from the exterior. To its rear are the tracks on which the building rotates – a detail that emphasises the movable character of the house. The staircase culminates in what looks like a lighthouse. With its railings and balconies, the entire façade seems to oscillate between a Bauhaus aesthetic and the suggestion of an ocean liner. There is a blend of Futurist modernity and the functional clarity of rationalism in which motion is not just a technical principle, but a defining design element as well.

The interior is also configured in line with a clear principle: all rooms gravitate to the inner corner of the “L”, while a corridor behind it leads the movement – a logical structure, as this corner always faces the sun. The spatial proportions correspond to the generous scale of a middle-class house, yet the architecture is surprisingly sober in its spatial quality. Its true appeal lies less in the design than in the idea of its mobility. The weight of the rotating structure can be precisely determined: 1,500 tonnes.

From the balcony to the tip of the cylinder, there is a wide view of the landscape. Formerly arranged along strict geometric lines, now – almost 100 years on – the garden is overgrown. Its monumental dimensions derive not so much from the proportions of the house as the geometry of the circle that the house describes as it rotates.

Apart from the rotation, one of the most remarkable aspects of the house is its construction – particularly the focus on reducing weight through the use of innovative materials. The walls consist of “eraclit” panels, a light, insulating material made from wood shavings, which is far superior to standard brickwork. Inside the walls are covered with textiles, underscoring their elegance and lightness. Invernizzi covered the façade with aluminium sheets arranged in small overlapping panels – like the fuselage of an aerorplane. This is a villa that is dynamic in every respect.

However, the choice of materials isn’t solely informed by considerations of weight; the flexibility of the structure is also important. To prevent cracks forming when the house rotates, the materials must be able to absorb movement. The textile wall cladding is elastic, and the small, overlapping façade elements allow for minimal shifts that are invisible to the eye. The same principle applies to the floor: the numerous gaps between the mosaic tiles and the narrow slats in the wooden floor ensure that the construction can move, in an architecture that literally travels in the direction of the sun without breaking up.

Current trends in architecture promote comfort by minimising the loss of heat – an approach that usually results in closed, very well insulated buildings. Villa Girasole, on the other hand, pursues a diametrically opposed principle of complete openness. Yet in its technical configuration, it points to a conception of comfort that was remarkable for the time. Built-in radiators, power points in the floor and motorised blinds that can be conveniently operated from the bed are testament to an advanced way of thinking that foretold modern living concepts.

Villa Girasole is a precursor to bio-architecture, in which focused use of sunlight lowers energy consumption. Yet evaluating it solely from a modern perspective would be short-sighted. Above all, the building reflects the extraordinary commitment of a creator who set himself a near-impossible task – recalling the iconic scene in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo in which a steamer is dragged over a mountain. A building mass of 5,000 m³, permanently connected to the water, sewage and electrical supply, that is designed to turn tirelessly toward the sun to maximise light and health. Today, the construction is static; repair has proven difficult, which only highlights the scale of this unique undertaking and the extraordinary spirit of innovation that first set this house-machine in motion.

Text: Aitor Fuentes Mendizabal & Igor Urdampilleta

Photos: Marta Tonelli

Image credits: Enrico Cano

Outside Verona, Angelo Invernizzi’s Villa Girasole rises at the end of a classic avenue of cypresses that winds up from the valley. Surrounded by vineyards and scattered farmhouses, the structure combines a futuristic vision with the aesthetic of an Italian manor house.

There is a carefully sequenced dramaturgy to the journey here: first you pass the simple caretaker’s house, then the winding path gradually reveals the silhouette of the villa. But before it is completely revealed, a pool with a concrete slide shaped like an elephant invites you to stop and pause. Then the house is revealed in all its glory: a building that rests on a monumental cylindrical drum, a volume that corresponds with that of the house.

The cylinder is like another plot within the plot, a raised stage for the actual architectural experiment in which Invernizzi’s technical masterwork becomes tangible: a 42-metre-high spiral staircase with integrated elevator, around which the whole house revolves – architecture in motion, anchored in its own rotation principle.

Villa Girasole, built between 1929 and 1935, served as a summer house for the maritime engineer and entrepreneur Angelo Invernizzi, his wife Lina who suffered from tuberculosis and their equally sick son – architecture designed to revolve around light and healing, not just mechanically but conceptually as well.

In the 1920s, medicine started focusing more on the sun, especially in the treatment of tuberculosis. Architecture, particularly hospital buildings, transformed from mere lodgings for patients to therapeutic instruments that were designed to actively aid recovery through thoughtful orientation and ventilation. One prominent example is Alvar Aalto’s 1929 design for the Paimio sanatorium in Finland, which influenced numerous hospital buildings of the time.

In Italy, this medical and architectonic transformation allied with Futurism as well as European rationalism – fruitful terrain for architectural experiments. It was in this context that Angelo Invernizzi made the bold decision to build a revolving house. Instead of a simple pavilion like the ones designed by French doctor Jean Saidman – including the revolving solarium erected in Aix-les-Bains in 1920 – he collaborated with architect Ettore Fagiuoli to design a multi-storey, L-shaped house. It rests on a cylindrical plinth which had to be partially embedded due to the sloping plot. This base provided the foundation for an architecture that literally followed the sun.

The dynamism of Villa Girasole is already apparent from the exterior. To its rear are the tracks on which the building rotates – a detail that emphasises the movable character of the house. The staircase culminates in what looks like a lighthouse. With its railings and balconies, the entire façade seems to oscillate between a Bauhaus aesthetic and the suggestion of an ocean liner. There is a blend of Futurist modernity and the functional clarity of rationalism in which motion is not just a technical principle, but a defining design element as well.

The interior is also configured in line with a clear principle: all rooms gravitate to the inner corner of the “L”, while a corridor behind it leads the movement – a logical structure, as this corner always faces the sun. The spatial proportions correspond to the generous scale of a middle-class house, yet the architecture is surprisingly sober in its spatial quality. Its true appeal lies less in the design than in the idea of its mobility. The weight of the rotating structure can be precisely determined: 1,500 tonnes.

From the balcony to the tip of the cylinder, there is a wide view of the landscape. Formerly arranged along strict geometric lines, now – almost 100 years on – the garden is overgrown. Its monumental dimensions derive not so much from the proportions of the house as the geometry of the circle that the house describes as it rotates.

Apart from the rotation, one of the most remarkable aspects of the house is its construction – particularly the focus on reducing weight through the use of innovative materials. The walls consist of “eraclit” panels, a light, insulating material made from wood shavings, which is far superior to standard brickwork. Inside the walls are covered with textiles, underscoring their elegance and lightness. Invernizzi covered the façade with aluminium sheets arranged in small overlapping panels – like the fuselage of an aerorplane. This is a villa that is dynamic in every respect.

However, the choice of materials isn’t solely informed by considerations of weight; the flexibility of the structure is also important. To prevent cracks forming when the house rotates, the materials must be able to absorb movement. The textile wall cladding is elastic, and the small, overlapping façade elements allow for minimal shifts that are invisible to the eye. The same principle applies to the floor: the numerous gaps between the mosaic tiles and the narrow slats in the wooden floor ensure that the construction can move, in an architecture that literally travels in the direction of the sun without breaking up.

Current trends in architecture promote comfort by minimising the loss of heat – an approach that usually results in closed, very well insulated buildings. Villa Girasole, on the other hand, pursues a diametrically opposed principle of complete openness. Yet in its technical configuration, it points to a conception of comfort that was remarkable for the time. Built-in radiators, power points in the floor and motorised blinds that can be conveniently operated from the bed are testament to an advanced way of thinking that foretold modern living concepts.

Villa Girasole is a precursor to bio-architecture, in which focused use of sunlight lowers energy consumption. Yet evaluating it solely from a modern perspective would be short-sighted. Above all, the building reflects the extraordinary commitment of a creator who set himself a near-impossible task – recalling the iconic scene in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo in which a steamer is dragged over a mountain. A building mass of 5,000 m³, permanently connected to the water, sewage and electrical supply, that is designed to turn tirelessly toward the sun to maximise light and health. Today, the construction is static; repair has proven difficult, which only highlights the scale of this unique undertaking and the extraordinary spirit of innovation that first set this house-machine in motion.

Angelo Invernizzi brought together architects, mechanical engineers, interior designers, sculptors and craftsmen who shared his belief in a new era to realise his visionary dream: architecture that follows the sun. After six years of construction, his “Sunflower” (girasole in Italian) was completed in 1935.

To make the building light and thus movable, Invernizzi used new materials such as concrete, fibre cement and lightweight wood shaving plates with cladding. They lent his functional masterpiece a sense of the monumental without weighing it down.

Invernizzi developed a system with three round tracks and 15 “roller skates”, driven by two diesel engines that rotate the 1,500-tonne structure at a rate of 4 mm per second – too slow to be perceptible as motion, but fast enough to follow the sun in nine hours and 20 minutes.

A plinth with a diameter of 44 metres topped by a rotating L-shaped building – connected by a central pivot. With a height of over 40 metres, the construction resembles a lighthouse.

The ground floor included a dining room, workrooms and a music room, while the kitchen, pantry and bathroom were positioned close to the central tower. The bedrooms were on the upper floor, a configuration that ensured changing light conditions throughout the day; all the rooms received the same dosage of sun and shade.

Reframe Sunshine

Mehr Interessantes zum Thema gibt’s hier.