The structure of adaptation.

An encounter in Barcelona in 25 scenes.

Finstral boss Joachim Oberrauch visits Aitor Fuentes and Igor Urdampilleta, two of the four founders and partners of the architectural practice Arquitectura-G, and discovers models, buildings and ideas. The conversation between them touches on topics such as indoor climate; places of transition that dissolve the demarcation between interior and exterior; stratification, protection, ventilation; and, of course, windows. But above all, it revolves around the art of adapting a built structure to new conditions – and lending structure to the adaptation (and the condition).

Text: Stefan Sippell

Photos: Gregori Civera

Image credits: Stefan Sippell, Arquitectura-G

1.

Joachim Oberrauch is, like many of his family members, a window enthusiast – or even a window nerd, you might say. When he walks around a city, he often looks up, always seeking out the windows. En route to the Arquitectura-G practice in Barcelona he spots numerous bay windows – and notices that many of the older windows are particularly tall. “So of course they let in more light,” he explains. “Rule of thumb: with tall windows you only need a third of the glass surface that you do for wide windows for the same degree of illumination. That may be one reason why they used to prefer narrower, very tall windows. More light, more warmth, less glass.”

2.

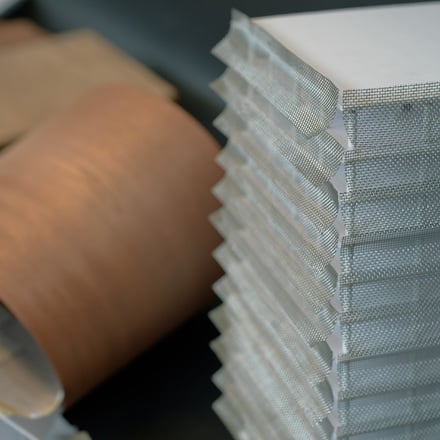

On the tables, on the shelves, from floor to ceiling – the Arquitectura-G studio is filled with models. “Unusual for the present day, certainly,” says Aitor Fuentes. They are made to a surprisingly large scale. “We prefer 1:20. As the commissions grew over time, we had to make the scale smaller, 1:50, sometimes 1:100.” – Joachim: “But is it still important for you to have models?” He knows the value of models himself, from the countless profile samples that Finstral makes for developing – and explaining – windows. Aitor: “Yes, models are absolutely essential. Not just for the developers. For us. The models don’t have to be pretty, it’s not like we need them for the archive. Unlike a 3D graphic on the computer, a model is never perfect, fortunately; they produce all sorts of unexpected perspectives, even while you’re constructing and assembling them. We can literally stick our heads inside our ideas. And it gives you a sense of the overall impact.”

Text: Stefan Sippell

Photos: Gregori Civera

Image credits: Stefan Sippell, Arquitectura-G

1.

Joachim Oberrauch is, like many of his family members, a window enthusiast – or even a window nerd, you might say. When he walks around a city, he often looks up, always seeking out the windows. En route to the Arquitectura-G practice in Barcelona he spots numerous bay windows – and notices that many of the older windows are particularly tall. “So of course they let in more light,” he explains. “Rule of thumb: with tall windows you only need a third of the glass surface that you do for wide windows for the same degree of illumination. That may be one reason why they used to prefer narrower, very tall windows. More light, more warmth, less glass.”

2.

On the tables, on the shelves, from floor to ceiling – the Arquitectura-G studio is filled with models. “Unusual for the present day, certainly,” says Aitor Fuentes. They are made to a surprisingly large scale. “We prefer 1:20. As the commissions grew over time, we had to make the scale smaller, 1:50, sometimes 1:100.” – Joachim: “But is it still important for you to have models?” He knows the value of models himself, from the countless profile samples that Finstral makes for developing – and explaining – windows. Aitor: “Yes, models are absolutely essential. Not just for the developers. For us. The models don’t have to be pretty, it’s not like we need them for the archive. Unlike a 3D graphic on the computer, a model is never perfect, fortunately; they produce all sorts of unexpected perspectives, even while you’re constructing and assembling them. We can literally stick our heads inside our ideas. And it gives you a sense of the overall impact.”

Ideal climate for discussion: Finstral boss Joachim Oberrauch (right) in Barcelona – and talking to Aitor Fuentes (left) and Igor Urdampilleta (centre), who founded Arquitectura-G in 2006 together with Jonathan Arnabat and Jordi Ayala-Bril. What began as a student project has now developed into an award-winning architectural practice – with a particular feel and flair for building with and within existing buildings. In their home town they are currently creating a new headquarters for the magazine Apartamento, for which they regularly write on architecture.

3.

Can we lift the lid on a secret here? Why the “G” after “Arquitectura"? Igor Urdampilleta: “The truth is that’s what the four of us called ourselves as a student group. We don’t know why. There are theories, but …” Aitor: “I think ‘a-g’ just sounded good to us. It could have been something else that we did together. A magazine.” Igor: “It began as a joke, and from that something more serious evolved. There’s no straightforward explanation for it.” Aitor: “Yes, the story is a little disappointing.” Or maybe not?

4.

There is something behind the name Finstral as well … although it’s not straightforward either. Joachim: “In part it’s the Italian finestra. But also the German Strahl, or beam – the light that comes through a window. Early on we even spelled ‘Finstrahl’ with an ‘h’. And my father, the founder, was excited by Finnish design back when he was a carpenter. Fin … he liked that association as well.”

5.

If you ask Arquitectura-G how the climate crisis has influenced their work, if you come at them with the ubiquitous buzzword of “climate-friendly construction”, at first they sound like they don’t want to give you a definitive answer. As though they can’t really warm to the issue. Or they’re playing it cool. Igor: “That isn’t our motivation for architecture, and it never was.” Aitor: “It’s never our starting point, it is only a part of our solution. We are engaged with structures and we try to solve problems that arise in this process at various levels. Addressing changing conditions, such as climate change, that’s an additional level.”

6.

For Arquitectura-G, thinking in levels isn’t just a metaphor, it can also be taken literally. Like the onion-skin principle for cladding. Igor: “In our works we often make the basic structure of the building visible. But that isn’t always easy, especially here in Spain, in Barcelona, especially now it’s getting even warmer. You have the structure, then you add the windows that obscure it. Because of the sun and the heat here, you need another level, an additional layer: a shade for the window. How do you build up these layers while still making the structure recognisable?”

7.

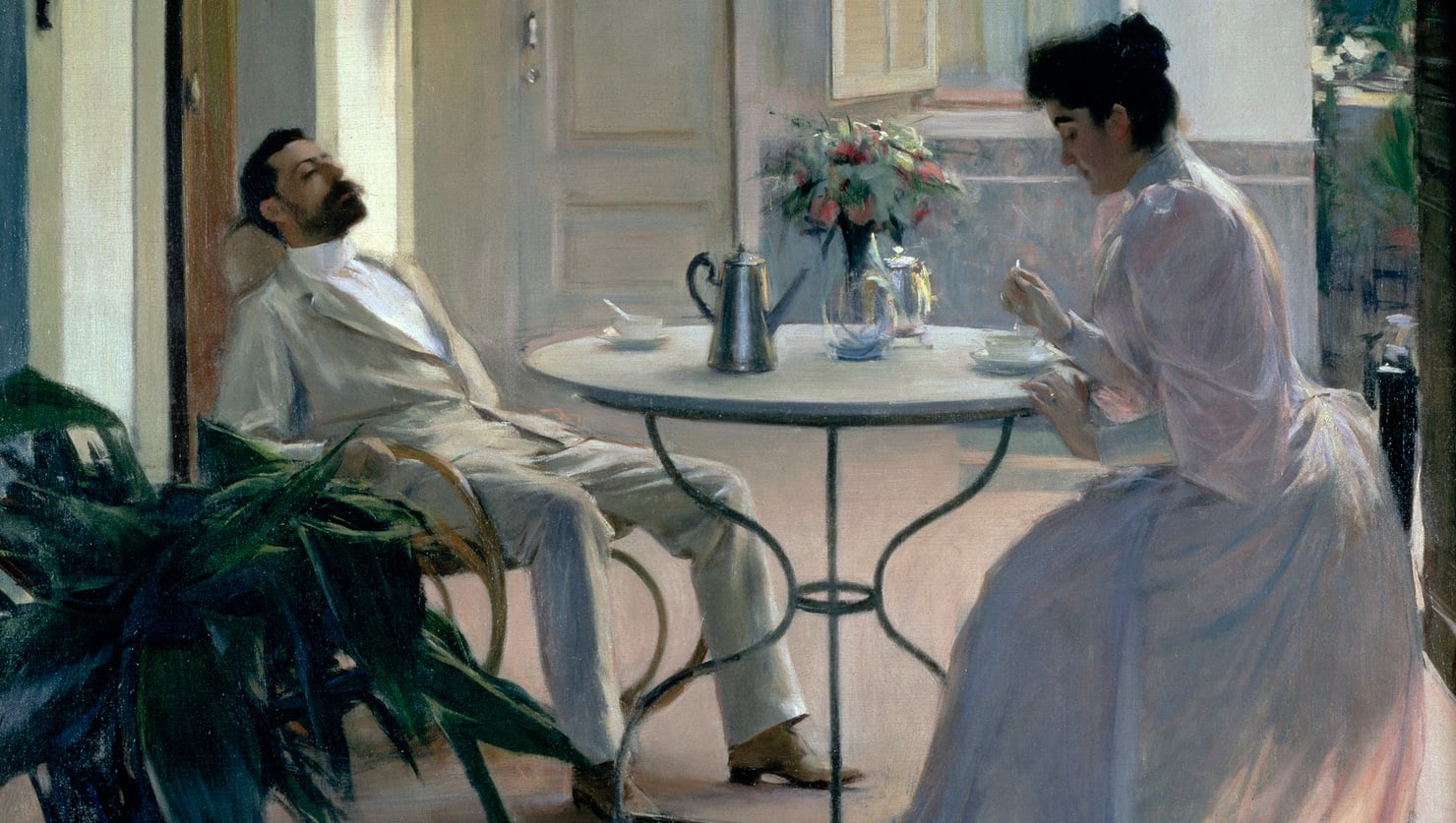

Aitor shows us a painting from 1892 by the famous Barcelona painter Ramon Casas. It’s called “Open Air Interior”. Here, on a terrace in the transitional zone between indoor and outdoor, a couple is sitting at a table. The man is leaning back with his eyes closed. She is stirring a cup, lost in her thoughts. Igor: “In our practice, working with this type of transitional space is more or less an obsession. It’s very important here that you think, plan and consciously design in multiple layers.” In this painting you see some of the layers that Igor is talking about. Wall, curtain, window, shutter, plants. Above them is the typical Barcelona sunshade – made up of thin wooden rods that can be rolled up. Joachim: “Of course, if you don’t have strong, thick walls, the indoor climate can be very dynamic. But you can regulate it with different levels, different layers.”

8.

That is exactly how Finstral sees windows as well, and also the way we construct them: in different layers, from the outside through the middle to the inside. Each of these assumes one of the functions that a modern window has to fulfil. And there are many of these functions. “At one point I counted them,” says Joachim. “And I came to 29 different functions.” Some of them are becoming more important with the climate crisis, depending on the region in which the window lives out its – ideally long – existence. “Impermeability to heavy rain, for example. Or protection against the sun, and thus heat. But it always comes down to the interplay between all the different functions.” Here, too, regulation is important – the command of stratification, if you will.

9.

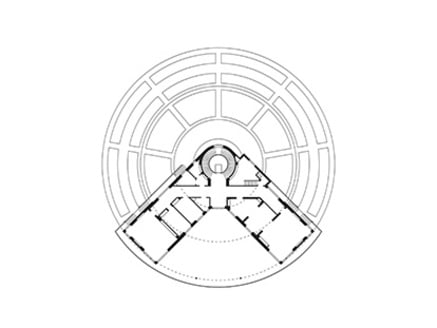

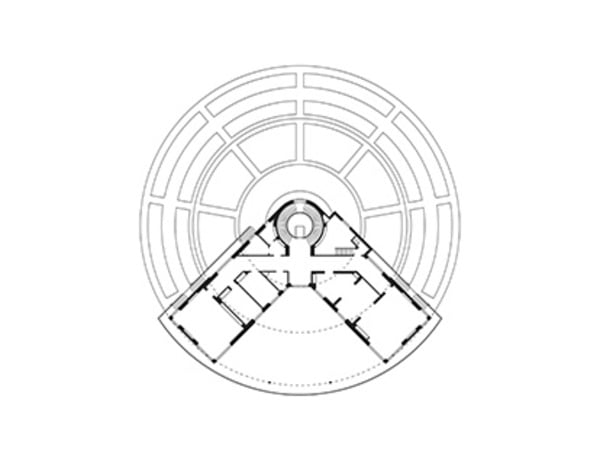

After a brief shower the sun is shining again in Barcelona, streaming through the windows of Arquitectura-G’s studio. It is shining directly on the model before us. “These will be the offices for Apartamento magazine,” says Igor. “In the heart of the Eixample district.” It’s a conversion, but a pretty radical conversion – with an opening in the roof to create a courtyard. Both halves of the building will feature frameless windows that can open, and as such disappear. The traditional sun protection is stretched or rolled as another layer over these windows, just as we saw in the Casas painting. Igor: “That is the good thing about the climate here in Barcelona. You can spend a lot of time with open windows, just with these wooden blinds.” Aitor: “In this city you really can sit outside for lunch a lot of the time, perhaps eight or nine months of the year. That would be a lot more difficult in Oslo.”

10.

It’s time for some common sense, which a lot of architectural projects could use as well. Aitor: “You know it right from the beginning. You know the orientation of the plot, you know the weather, the climate in the city. That is all on the table on the first day. So you don’t suggest stupid things that don’t make sense for the climate, do you?”

11.

However, it is precisely at this point that demands come into play – and sometimes they can be disruptive. Aitor: “People always want a perfect indoor temperature. But I’m not sure that always makes sense from a carbon perspective – if it’s a holiday house, for example. Perhaps it’s not really a good idea to spend a fortune on 60-centimetre walls that take an enormous amount of carbon to produce. Perhaps it would be better to just light a fire now and then.”

12.

And architects, just like window manufacturers, have to deal with legal requirements, which are becoming more copious, more detailed and more inflexible all the time. Igor: “We really need to cut out some regulation. Like I said, it is already our responsibility to consider the conditions, and that includes climatic conditions. We don’t need rules for that! Which is why it’s even more absurd that the exact same regulations apply in the Pyrenees, in northern Spain, and in the middle of the country.” You can see it in numerous contemporary buildings: “The architects concentrate on following the rules instead of thinking about the architecture.” – “It’s the same with cars,” adds Joachim. “The fact that so many cars look alike these days is to do with the rules. When you have too many standards it’s harder to be creative. Which is no small danger if we want to develop and advance.”

13.

On the other hand: isn’t it the obstacles that make creativity possible in the first place? The limits that we have to test? Arquitectura-G’s designs certainly seem to confirm this thesis. Their models work through all the different ways you can think in structures and design in layers – while also ensuring protection and ventilation.

13.1

Another building with the typical Barcelona blind. “Light,” says Aitor. “Light in terms of weight, but also light work to roll up or down. You open the window and the sunshade hangs in front of the balcony. So you have air.” Joachim: “… and you can see the street.”

13.2

A community centre in Benin, western Africa. The temperature here is a constant 30 degrees throughout the year; and it rains – or not. Walls made of clay, all the rooms open: cross ventilation! The roof keeps the building dry, dispenses shade and – ingeniously – also serves as a running track.

13.3

An apartment building in Albania. The design combines two needs: protection from falling and protection from direct sunlight. The balcony railings continue downwards, opening out to become shades; fixed, transparent.

Can we lift the lid on a secret here? Why the “G” after “Arquitectura"? Igor Urdampilleta: “The truth is that’s what the four of us called ourselves as a student group. We don’t know why. There are theories, but …” Aitor: “I think ‘a-g’ just sounded good to us. It could have been something else that we did together. A magazine.” Igor: “It began as a joke, and from that something more serious evolved. There’s no straightforward explanation for it.” Aitor: “Yes, the story is a little disappointing.” Or maybe not?

4.

There is something behind the name Finstral as well … although it’s not straightforward either. Joachim: “In part it’s the Italian finestra. But also the German Strahl, or beam – the light that comes through a window. Early on we even spelled ‘Finstrahl’ with an ‘h’. And my father, the founder, was excited by Finnish design back when he was a carpenter. Fin … he liked that association as well.”

5.

If you ask Arquitectura-G how the climate crisis has influenced their work, if you come at them with the ubiquitous buzzword of “climate-friendly construction”, at first they sound like they don’t want to give you a definitive answer. As though they can’t really warm to the issue. Or they’re playing it cool. Igor: “That isn’t our motivation for architecture, and it never was.” Aitor: “It’s never our starting point, it is only a part of our solution. We are engaged with structures and we try to solve problems that arise in this process at various levels. Addressing changing conditions, such as climate change, that’s an additional level.”

6.

For Arquitectura-G, thinking in levels isn’t just a metaphor, it can also be taken literally. Like the onion-skin principle for cladding. Igor: “In our works we often make the basic structure of the building visible. But that isn’t always easy, especially here in Spain, in Barcelona, especially now it’s getting even warmer. You have the structure, then you add the windows that obscure it. Because of the sun and the heat here, you need another level, an additional layer: a shade for the window. How do you build up these layers while still making the structure recognisable?”

7.

Aitor shows us a painting from 1892 by the famous Barcelona painter Ramon Casas. It’s called “Open Air Interior”. Here, on a terrace in the transitional zone between indoor and outdoor, a couple is sitting at a table. The man is leaning back with his eyes closed. She is stirring a cup, lost in her thoughts. Igor: “In our practice, working with this type of transitional space is more or less an obsession. It’s very important here that you think, plan and consciously design in multiple layers.” In this painting you see some of the layers that Igor is talking about. Wall, curtain, window, shutter, plants. Above them is the typical Barcelona sunshade – made up of thin wooden rods that can be rolled up. Joachim: “Of course, if you don’t have strong, thick walls, the indoor climate can be very dynamic. But you can regulate it with different levels, different layers.”

8.

That is exactly how Finstral sees windows as well, and also the way we construct them: in different layers, from the outside through the middle to the inside. Each of these assumes one of the functions that a modern window has to fulfil. And there are many of these functions. “At one point I counted them,” says Joachim. “And I came to 29 different functions.” Some of them are becoming more important with the climate crisis, depending on the region in which the window lives out its – ideally long – existence. “Impermeability to heavy rain, for example. Or protection against the sun, and thus heat. But it always comes down to the interplay between all the different functions.” Here, too, regulation is important – the command of stratification, if you will.

9.

After a brief shower the sun is shining again in Barcelona, streaming through the windows of Arquitectura-G’s studio. It is shining directly on the model before us. “These will be the offices for Apartamento magazine,” says Igor. “In the heart of the Eixample district.” It’s a conversion, but a pretty radical conversion – with an opening in the roof to create a courtyard. Both halves of the building will feature frameless windows that can open, and as such disappear. The traditional sun protection is stretched or rolled as another layer over these windows, just as we saw in the Casas painting. Igor: “That is the good thing about the climate here in Barcelona. You can spend a lot of time with open windows, just with these wooden blinds.” Aitor: “In this city you really can sit outside for lunch a lot of the time, perhaps eight or nine months of the year. That would be a lot more difficult in Oslo.”

10.

It’s time for some common sense, which a lot of architectural projects could use as well. Aitor: “You know it right from the beginning. You know the orientation of the plot, you know the weather, the climate in the city. That is all on the table on the first day. So you don’t suggest stupid things that don’t make sense for the climate, do you?”

11.

However, it is precisely at this point that demands come into play – and sometimes they can be disruptive. Aitor: “People always want a perfect indoor temperature. But I’m not sure that always makes sense from a carbon perspective – if it’s a holiday house, for example. Perhaps it’s not really a good idea to spend a fortune on 60-centimetre walls that take an enormous amount of carbon to produce. Perhaps it would be better to just light a fire now and then.”

12.

And architects, just like window manufacturers, have to deal with legal requirements, which are becoming more copious, more detailed and more inflexible all the time. Igor: “We really need to cut out some regulation. Like I said, it is already our responsibility to consider the conditions, and that includes climatic conditions. We don’t need rules for that! Which is why it’s even more absurd that the exact same regulations apply in the Pyrenees, in northern Spain, and in the middle of the country.” You can see it in numerous contemporary buildings: “The architects concentrate on following the rules instead of thinking about the architecture.” – “It’s the same with cars,” adds Joachim. “The fact that so many cars look alike these days is to do with the rules. When you have too many standards it’s harder to be creative. Which is no small danger if we want to develop and advance.”

13.

On the other hand: isn’t it the obstacles that make creativity possible in the first place? The limits that we have to test? Arquitectura-G’s designs certainly seem to confirm this thesis. Their models work through all the different ways you can think in structures and design in layers – while also ensuring protection and ventilation.

13.1

Another building with the typical Barcelona blind. “Light,” says Aitor. “Light in terms of weight, but also light work to roll up or down. You open the window and the sunshade hangs in front of the balcony. So you have air.” Joachim: “… and you can see the street.”

13.2

A community centre in Benin, western Africa. The temperature here is a constant 30 degrees throughout the year; and it rains – or not. Walls made of clay, all the rooms open: cross ventilation! The roof keeps the building dry, dispenses shade and – ingeniously – also serves as a running track.

13.3

An apartment building in Albania. The design combines two needs: protection from falling and protection from direct sunlight. The balcony railings continue downwards, opening out to become shades; fixed, transparent.

7.

9.

13.1

13.2

13.3

13.4

A house in the Pyrenees. Aitor: “We’re working on this right now. It’s an extension. It’s colder in this region, they get snow. That’s why the roof is the key structure. We are thinking about a type of pavilion; and we are considering sinking a part of the building into the ground – to reduce the expression of the house to just the roof.”

14.

So we need to adapt to the local conditions – including (but not limited to) the conditions that come with the climate crisis. And to adapt to the rules, requirements and standards where necessary. At the same time, the goal is to understand this process of adaptation as a creative process, use the scope you have, and expand it so new ideas can develop. It’s called evolution, but an evolution that is deliberately induced and consciously guided. Demanding? Igor: “It’s harder to be bold these days.”

15.

With that we head out from modelling buildings to their execution – in Barcelona. We are standing outside a five-storey residential building that Arquitectura-G designed, a new build on Carrer de la Llacuna in the district of Poblenou. Strict regulations determined that it had to align with the look of the existing buildings around it, so the scope for creativity in the façade and window design was highly circumscribed. Igor: “We managed to include windows with frames that are invisible from outside – they look highly reduced, like glazed holes in the wall. Combined with simple louvre blinds for shade.”

16.

But the defining structural element of the Llacuna corner building is elsewhere: in the staircase. For fire safety reasons it had to be ventilated, but the usual position along the façade would have deprived the apartments of precious space for windows and balconies. Aitor: “So we constructed a spiral staircase and put it in the middle. The staircase has an open connection to the façade on each storey. And on top there is a glass roof that is also unsealed, but wider than the diameter of the staircase. So it stays dry, but there is a draught, like you have in a fireplace.” With everything open all the time, all year round? “In this region, absolutely.”

17.

There are two apartments on each storey, each apartment wrapped around half of the curving staircase. Only on the top storey do they have the full space in a single apartment, where the residents go round in circles, so to speak. Moving outwards from the centre, first you have the building technology in the wall, then the large kitchen and living area and the smaller bedrooms and bathrooms on two levels. It builds up layer by layer until you arrive at the windows, balconies and exit to the roof terrace. It is not just the blinds (and the air conditioning) that are important for the indoor climate, but also the tall deciduous trees in the street. In summer the leaves cast shade, in winter more sunlight shines through the bare branches.

18.

“Because we had to match the façades,” says Igor, “we decided on a large, circular incision in the centre.” Joachim: “Good solution.” And one that garnered them Spain’s prestigious FAD prize for architecture (2022).

19.

How radical can you get? In the past, and today? During our Barcelona visit, Aitor and Igor also show us La Fábrica. And they tell us all about this former cement factory outside the city which was acquired in 1973 by the (later) architecture legend Ricardo Bofill, and how since then it has been continuously refurbished, transformed, magicked into his office, his home, his think tank, his fairytale palace. In the years before Bofill’s death in 2022, the young practice Arquitectura-G was well acquainted with him; it has since carried out joint projects with Bofill’s company RBTA. “It must have been wild in the early years of La Fábrica,” says Igor. “Bofill and his friends were young. They blew up a lot of the factory themselves to gain space. They would throw parties.” Aitor: “The theme would be gin and tonic and dynamite. Hey, what could go wrong?”

20.

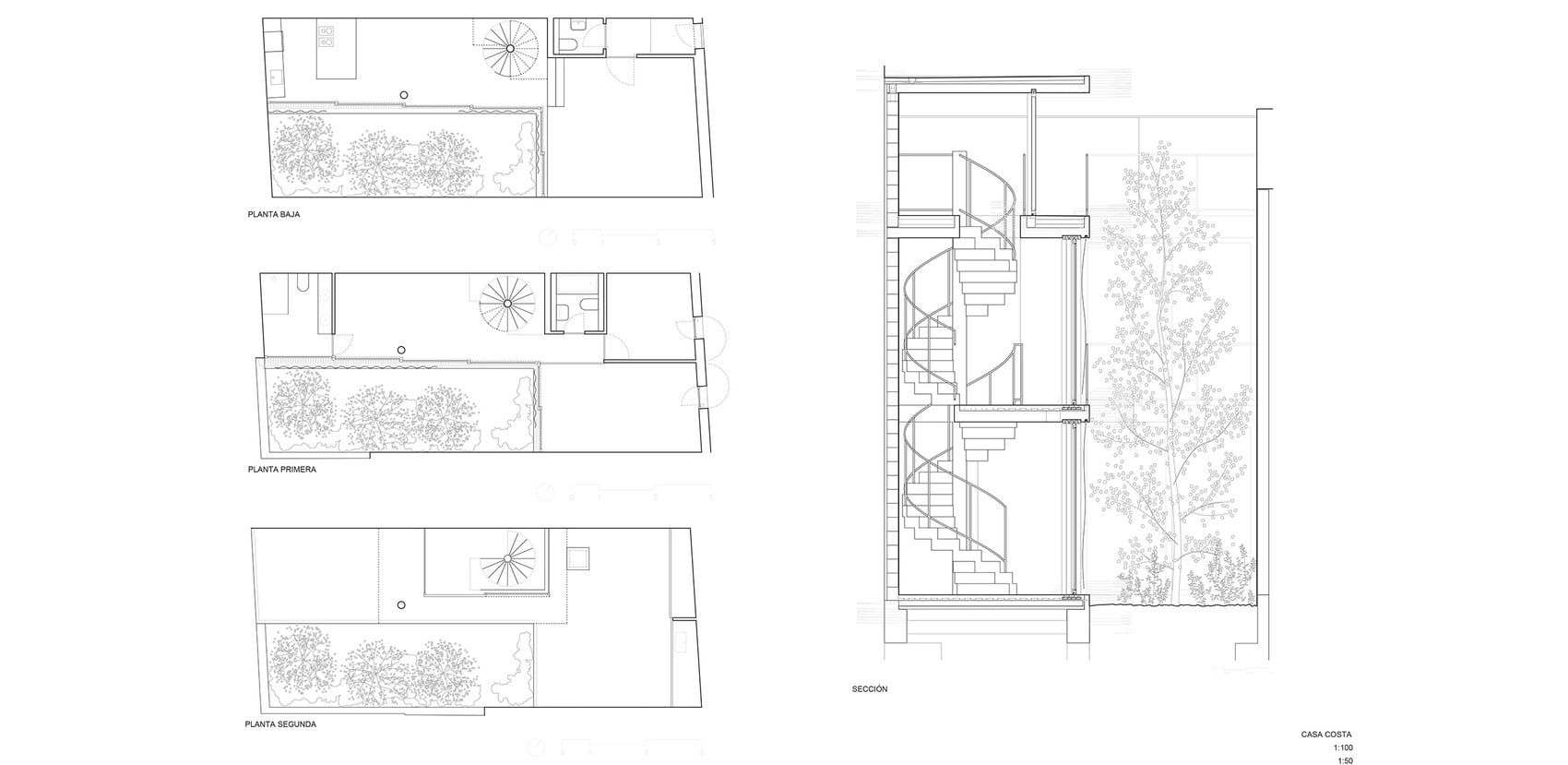

And you can still find this radical architectural spirit today, in this case on a small residential street in Barcelona. But you really have to be looking for it; it’s quieter around here, with less traffic and no tourists. One normal little house after another, some taller, some shorter, some newer, some older, all of them with normal windows, doors, shutters, garage doors. And then, all of a sudden: the white wall. “Casa Costa” is the name of the house.

21.

Aitor: “Originally we were going to renovate the house that stood here. The planning was complete. Then we noticed that the core of the structure was much too damaged. So we had to tell the owners – the family who lived there, and still does – that it wasn’t worth the effort. That it was better to tear it down and build from scratch. Even if it would take an extra year. In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. At first it was a major shock …” He smiles: “… a much bigger shock than our design.”

22.

From the street: all in white. And (almost) completely sealed. Sure, you can open up the door with its top light, the two building technology hatches and the two shutters on the first floor; the white paint, which otherwise has a reflective function to prevent overheating, draws the sun into the bedrooms. But the main thing is that the openings in the wall can disappear. Igor: “Our idea with the façade was not to establish a relation with the outside, but instead to shut the house off on this side, to protect it, render it anonymous.” Aitor: “As though there were no façade at all. Just a wall.”

23.

Is the electricity cable hanging there deliberate? Igor: “Yes, at first we didn’t want to have it at all, a nightmare. But there was no choice. Then we deliberately positioned it like that. I like the cable now. It lends the wall a certain … vibrancy.”

24.

And on our visit, Casa Costa fulfils its function: it’s all sealed up. We can’t get in today. Instead we have the interior explained to us and presented in photos. Inside, everything is different, everything is open. Entirely aligned with the southern European patio tradition, but more rigorously applied. House and courtyard – a collective space, one great in-between. Aitor: “Here the house opens up for its own interior life.” The large glass elements can be completely pushed to one side. In their place is a thin, movable layer: long white curtains. Igor: “I like this image where only the curtains are closed. The layer between inside and outside consists of nothing more than this panel of material which is just millimetres wide – at this moment it becomes the façade. That means depending on the weather, the climate and the season, the façade is the curtain. Or the façade becomes a window without a curtain. Or the window with the curtain are the façade.”

25.

Casa Costa doesn’t need technical air conditioning. But that wasn’t the goal of the architectural design, more of a side effect. Aitor: “Getting it completely open inside and completely closed outside was the motivation behind the project. How do we make it happen?“ Igor: “Only then did we address the climatic situation.” The house seems to fit in perfectly: in this place and in this city, with the climate and its crisis … precisely because it doesn’t fit in. You could call it the structure (and the structuring) of adaptation. Joachim: “Ultimately, that is precisely the challenge: each building has its own problem that you have to solve. In its own location. In its own environment. Under its own conditions.”

A house in the Pyrenees. Aitor: “We’re working on this right now. It’s an extension. It’s colder in this region, they get snow. That’s why the roof is the key structure. We are thinking about a type of pavilion; and we are considering sinking a part of the building into the ground – to reduce the expression of the house to just the roof.”

14.

So we need to adapt to the local conditions – including (but not limited to) the conditions that come with the climate crisis. And to adapt to the rules, requirements and standards where necessary. At the same time, the goal is to understand this process of adaptation as a creative process, use the scope you have, and expand it so new ideas can develop. It’s called evolution, but an evolution that is deliberately induced and consciously guided. Demanding? Igor: “It’s harder to be bold these days.”

15.

With that we head out from modelling buildings to their execution – in Barcelona. We are standing outside a five-storey residential building that Arquitectura-G designed, a new build on Carrer de la Llacuna in the district of Poblenou. Strict regulations determined that it had to align with the look of the existing buildings around it, so the scope for creativity in the façade and window design was highly circumscribed. Igor: “We managed to include windows with frames that are invisible from outside – they look highly reduced, like glazed holes in the wall. Combined with simple louvre blinds for shade.”

16.

But the defining structural element of the Llacuna corner building is elsewhere: in the staircase. For fire safety reasons it had to be ventilated, but the usual position along the façade would have deprived the apartments of precious space for windows and balconies. Aitor: “So we constructed a spiral staircase and put it in the middle. The staircase has an open connection to the façade on each storey. And on top there is a glass roof that is also unsealed, but wider than the diameter of the staircase. So it stays dry, but there is a draught, like you have in a fireplace.” With everything open all the time, all year round? “In this region, absolutely.”

17.

There are two apartments on each storey, each apartment wrapped around half of the curving staircase. Only on the top storey do they have the full space in a single apartment, where the residents go round in circles, so to speak. Moving outwards from the centre, first you have the building technology in the wall, then the large kitchen and living area and the smaller bedrooms and bathrooms on two levels. It builds up layer by layer until you arrive at the windows, balconies and exit to the roof terrace. It is not just the blinds (and the air conditioning) that are important for the indoor climate, but also the tall deciduous trees in the street. In summer the leaves cast shade, in winter more sunlight shines through the bare branches.

18.

“Because we had to match the façades,” says Igor, “we decided on a large, circular incision in the centre.” Joachim: “Good solution.” And one that garnered them Spain’s prestigious FAD prize for architecture (2022).

19.

How radical can you get? In the past, and today? During our Barcelona visit, Aitor and Igor also show us La Fábrica. And they tell us all about this former cement factory outside the city which was acquired in 1973 by the (later) architecture legend Ricardo Bofill, and how since then it has been continuously refurbished, transformed, magicked into his office, his home, his think tank, his fairytale palace. In the years before Bofill’s death in 2022, the young practice Arquitectura-G was well acquainted with him; it has since carried out joint projects with Bofill’s company RBTA. “It must have been wild in the early years of La Fábrica,” says Igor. “Bofill and his friends were young. They blew up a lot of the factory themselves to gain space. They would throw parties.” Aitor: “The theme would be gin and tonic and dynamite. Hey, what could go wrong?”

20.

And you can still find this radical architectural spirit today, in this case on a small residential street in Barcelona. But you really have to be looking for it; it’s quieter around here, with less traffic and no tourists. One normal little house after another, some taller, some shorter, some newer, some older, all of them with normal windows, doors, shutters, garage doors. And then, all of a sudden: the white wall. “Casa Costa” is the name of the house.

21.

Aitor: “Originally we were going to renovate the house that stood here. The planning was complete. Then we noticed that the core of the structure was much too damaged. So we had to tell the owners – the family who lived there, and still does – that it wasn’t worth the effort. That it was better to tear it down and build from scratch. Even if it would take an extra year. In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. At first it was a major shock …” He smiles: “… a much bigger shock than our design.”

22.

From the street: all in white. And (almost) completely sealed. Sure, you can open up the door with its top light, the two building technology hatches and the two shutters on the first floor; the white paint, which otherwise has a reflective function to prevent overheating, draws the sun into the bedrooms. But the main thing is that the openings in the wall can disappear. Igor: “Our idea with the façade was not to establish a relation with the outside, but instead to shut the house off on this side, to protect it, render it anonymous.” Aitor: “As though there were no façade at all. Just a wall.”

23.

Is the electricity cable hanging there deliberate? Igor: “Yes, at first we didn’t want to have it at all, a nightmare. But there was no choice. Then we deliberately positioned it like that. I like the cable now. It lends the wall a certain … vibrancy.”

24.

And on our visit, Casa Costa fulfils its function: it’s all sealed up. We can’t get in today. Instead we have the interior explained to us and presented in photos. Inside, everything is different, everything is open. Entirely aligned with the southern European patio tradition, but more rigorously applied. House and courtyard – a collective space, one great in-between. Aitor: “Here the house opens up for its own interior life.” The large glass elements can be completely pushed to one side. In their place is a thin, movable layer: long white curtains. Igor: “I like this image where only the curtains are closed. The layer between inside and outside consists of nothing more than this panel of material which is just millimetres wide – at this moment it becomes the façade. That means depending on the weather, the climate and the season, the façade is the curtain. Or the façade becomes a window without a curtain. Or the window with the curtain are the façade.”

25.

Casa Costa doesn’t need technical air conditioning. But that wasn’t the goal of the architectural design, more of a side effect. Aitor: “Getting it completely open inside and completely closed outside was the motivation behind the project. How do we make it happen?“ Igor: “Only then did we address the climatic situation.” The house seems to fit in perfectly: in this place and in this city, with the climate and its crisis … precisely because it doesn’t fit in. You could call it the structure (and the structuring) of adaptation. Joachim: “Ultimately, that is precisely the challenge: each building has its own problem that you have to solve. In its own location. In its own environment. Under its own conditions.”

13.4

15

16

17

19

20

22

24

Reframe Sunshine

Find more helpful information on this topic here.