The shift worker.

A room with a tree. Junya Ishigami’s architecture brings nature inside.

The Japanese architect Junya Ishigami is a master of atmospheric staging. His houses bring the natural world layer by layer from the outside to the inside − or integrate it into the construction as a readymade.

Interview: Wojciech Czaja

How would you describe the view from your office?

Ishigami: That’s a very unpleasant question to start with! We have no windows, no daylight, no views. Our office is located in the basement, in a former nightclub in Tokyo’s Roppongi district.

That sounds rather gloomy. How did that come about?

When I opened my office in 2004, I had two options: either small, with a view, or large with no view. I chose the latter. The office is now 400 metres square with ample space to work in, especially for the models. Many of our projects are created in three-dimensional miniature illustrations of reality.

You celebrate daylight with your architecture and play with visual axes, staging nature indoors. Is that not a clear contradiction of the place where all these projects come about?

As an architect your mind’s eye and atmospheric imagination have free rein. But you are right: the office situation could be better. But I console myself with the thought that, from my apartment, I can look out at a little house with lots of greenery all around.

All very Japanese.

Yes, almost like a Shinto shrine in the middle of the city.

In Japan, the visual relationships between indoor and outdoor spaces have always played a major role − in houses, in temples, in gardens. Where does this tradition come from?

In Japanese architectural history, the classical window as it is known in the Western world did not originally exist. A traditional house would consist of a load-bearing construction and filling elements, sometimes fixed and sometimes movable, sometimes solid and sometimes transparent, or at least translucent. Rooms were mostly separated by means of sliding doors made of tensioned rice paper. The elements could be moved according to taste, thus changing not only the room sizes and room functions, but also controlling the openness and intimacy of each individual room. It involves a dynamic play of light and space.

The façades too are similarly flexible...

Exactly, instead of conventional windows and doors, the façade area has several layers of movable skins of varying degrees of translucency, allowing the occupant to create different lighting moods − from light to dark. I find the finest example of this to be where transitions softly flow into one another at the interface between light and shadow. This is one of the stand-out features of our historic temples and gardens.

Do you have a favourite from those early years?

My favourite is the Ise Shrine in the Mie prefecture. This is one of the oldest gardens in Japan and today consists of both old and new shrines. The interplay of layers is by no means limited to the façade, which is something that is common to all buildings. Every single tree, the many branches, twigs, leaves, depicted as silhouettes on the rice paper, add another dimension to the sense of space. I find it deeply fascinating how nature has its effect on architecture.

Would you describe the surrounding natural world as a part of Japanese architecture?

Absolutely! Architecture and nature merge seamlessly, intermeshing and becoming one. I would even go so far as to say: nature in Japan does not just mean the environment, it is an intangible building material without which Japanese architecture would be unthinkable.

Interview: Wojciech Czaja

How would you describe the view from your office?

Ishigami: That’s a very unpleasant question to start with! We have no windows, no daylight, no views. Our office is located in the basement, in a former nightclub in Tokyo’s Roppongi district.

That sounds rather gloomy. How did that come about?

When I opened my office in 2004, I had two options: either small, with a view, or large with no view. I chose the latter. The office is now 400 metres square with ample space to work in, especially for the models. Many of our projects are created in three-dimensional miniature illustrations of reality.

You celebrate daylight with your architecture and play with visual axes, staging nature indoors. Is that not a clear contradiction of the place where all these projects come about?

As an architect your mind’s eye and atmospheric imagination have free rein. But you are right: the office situation could be better. But I console myself with the thought that, from my apartment, I can look out at a little house with lots of greenery all around.

All very Japanese.

Yes, almost like a Shinto shrine in the middle of the city.

In Japan, the visual relationships between indoor and outdoor spaces have always played a major role − in houses, in temples, in gardens. Where does this tradition come from?

In Japanese architectural history, the classical window as it is known in the Western world did not originally exist. A traditional house would consist of a load-bearing construction and filling elements, sometimes fixed and sometimes movable, sometimes solid and sometimes transparent, or at least translucent. Rooms were mostly separated by means of sliding doors made of tensioned rice paper. The elements could be moved according to taste, thus changing not only the room sizes and room functions, but also controlling the openness and intimacy of each individual room. It involves a dynamic play of light and space.

The façades too are similarly flexible...

Exactly, instead of conventional windows and doors, the façade area has several layers of movable skins of varying degrees of translucency, allowing the occupant to create different lighting moods − from light to dark. I find the finest example of this to be where transitions softly flow into one another at the interface between light and shadow. This is one of the stand-out features of our historic temples and gardens.

Do you have a favourite from those early years?

My favourite is the Ise Shrine in the Mie prefecture. This is one of the oldest gardens in Japan and today consists of both old and new shrines. The interplay of layers is by no means limited to the façade, which is something that is common to all buildings. Every single tree, the many branches, twigs, leaves, depicted as silhouettes on the rice paper, add another dimension to the sense of space. I find it deeply fascinating how nature has its effect on architecture.

Would you describe the surrounding natural world as a part of Japanese architecture?

Absolutely! Architecture and nature merge seamlessly, intermeshing and becoming one. I would even go so far as to say: nature in Japan does not just mean the environment, it is an intangible building material without which Japanese architecture would be unthinkable.

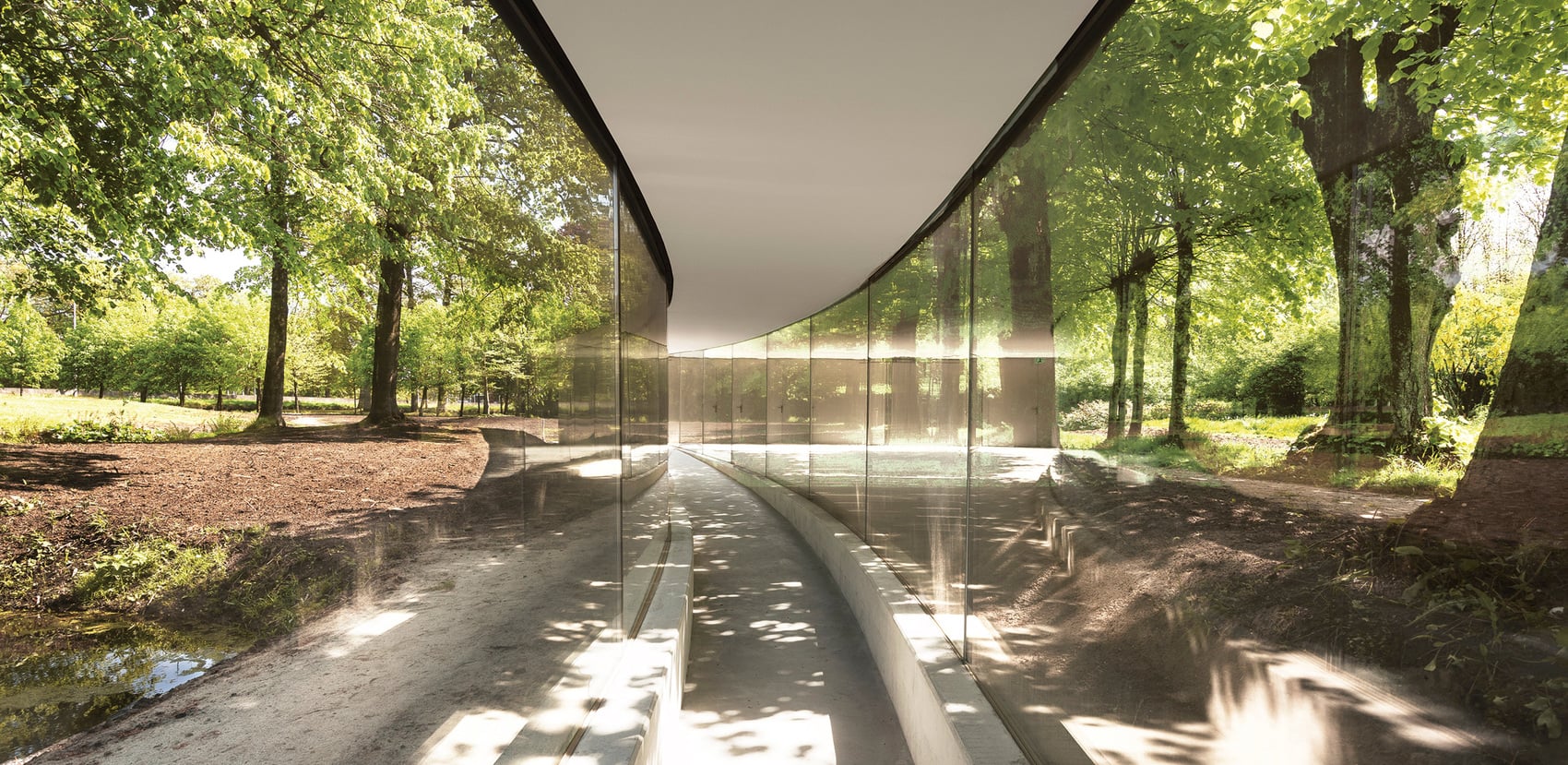

Blending into the landscape: visitor centre (2017) in the Groot Vijversburg park in the Netherlands.

Can this historical view of nature as an architectural building material still be found today?

Less and less. More’s the pity! Instead of the complex façades with their broken, blurred, fluid boundaries, there arose an architecture of rigid framing, without any dynamic creative tools for distinguishing between inside and outside. Don’t get me wrong, I find this design appealing and often just as high quality in its realisation – but it now has little to do with the historical, ever-changing complexity.

Where does this new rigid architecture come from?

There is one very simple reason: spatial efficiency. Multi-layered façades with different layers need firstly, a certain depth and secondly, a certain size of space so that this aesthetic realisation will become consciously perceptible. In times of growing populations and rising house prices, space is an expensive commodity and it thus becomes increasingly difficult to think in large-scale terms. We have to be content with more efficient solutions.

And your reaction to this efficiency?

I try to retain a certain generosity in my thinking and critical questioning. My approach has changed a lot in recent years. In the past I tried to bring nature and the outdoor world into the interior of the house – using windows, wall openings, and deliberately set visual axes. But that often no longer works, as many places where we live have no more contact with nature, nor even with the surrounding city. My office is a perfect example of this. That is why I started to stage nature in interiors and create a certain atmosphere of the outdoors.

How do you do that?

On the one hand, by incorporating into my architecture green, i.e. living, organic matter. In my “House with Plants” for a young Tokyo family, for example, I placed clods of earth in the middle of the living room and created a forest floor with bushes and trees on this. On the other hand, I use inorganic building blocks from nature and adjust these or use them as architectural readymades.

You will have to explain further!

In Dari, in south-west China, I am currently planning a coherent ensemble of eight weekend cottages with a total area of around 4,000 square metres. Nature in this truly impressive landscape consists of large, round stones, and boulders, some three to four metres high, that are scattered in the forest. I use these boulders for example as supports and pillars for a concrete roof that will float over them. The stones are neither moved in position nor worked, but used just as we find them. The building is then simply glazed all around. That’s it.

Is glass an important building material for you?

Yes, I use a lot of glass, because it possesses numerous advantages that other building materials do not have. But glass is no more important than wood, brick, steel or concrete. It is simply different.

The restaurant that you are currently building in Yamaguchi is also highly archaic in style.

Yes, it is a little French restaurant that has some of the feel of an artificially created cave system. I got the construction workers to dig holes directly on the site, into which we then placed reinforcement cages, then filled them with concrete. In this way we used the soil as formwork. Finally, the soil underneath and to the side was removed and the entire structure given all-round glazing. I really like this project, because here the underground natural world lives on as a positive impression in concrete. The structure of the soil can still clearly be seen in the surface of the concrete.

What did the clients say to these unusual notions?

I hope they really like them! I think we have to constantly develop our understanding of architecture, because cities are changing – and with them the living conditions and creative possibilities. The more nature is pushed back, the more we have to be careful to create a certain natural atmosphere. That’s what I stand for with my architecture.

Many architects – especially in Japan – respond to this change in circumstances with maximum transparency. The result is often fully glazed buildings, such as the House Na by Sou Fujimoto.

A fantastic house! These are exciting ideas that work with the total dissolving of the boundaries between inside and outside, private and public sphere. I personally find this concept too hard. I prefer a gentle, multi-layered transition, such as we know from our own architectural history. This does not mean that we are obliged to use rice paper walls. We can also work with light, with spatial depth, with deliberately staged views and silhouettes...

...or even with underground caves.

You said it! The most important building block in architecture and urban planning is diversity. We live in a century of density. Cities are getting ever bigger and more densely populated. Our job is to manage this development intelligently. There are so many different concepts for this. I focus on mine.

The architect as designer – not merely of houses, but above all of society?

I want my kind of architecture to contribute, at least minimally, to the improvement and enrichment of the world. I want with my projects to create a small world on a large scale. I want to enlarge the world.

Junya Ishigami, born in 1974 in Kanagawa prefecture. He studied architecture at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. From 2000 to 2004 he worked for the architectural firm of SANAA. In 2004 he founded his own firm, junya.ishigami + associates. In 2008 and 2010, he participated in the Venice Biennale of Architecture and was awarded the Golden Lion for his contribution. Since 2010 he has been Associate Professor at Tohoku University in Japan and, since 2014, guest critic at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, USA.

Less and less. More’s the pity! Instead of the complex façades with their broken, blurred, fluid boundaries, there arose an architecture of rigid framing, without any dynamic creative tools for distinguishing between inside and outside. Don’t get me wrong, I find this design appealing and often just as high quality in its realisation – but it now has little to do with the historical, ever-changing complexity.

Where does this new rigid architecture come from?

There is one very simple reason: spatial efficiency. Multi-layered façades with different layers need firstly, a certain depth and secondly, a certain size of space so that this aesthetic realisation will become consciously perceptible. In times of growing populations and rising house prices, space is an expensive commodity and it thus becomes increasingly difficult to think in large-scale terms. We have to be content with more efficient solutions.

And your reaction to this efficiency?

I try to retain a certain generosity in my thinking and critical questioning. My approach has changed a lot in recent years. In the past I tried to bring nature and the outdoor world into the interior of the house – using windows, wall openings, and deliberately set visual axes. But that often no longer works, as many places where we live have no more contact with nature, nor even with the surrounding city. My office is a perfect example of this. That is why I started to stage nature in interiors and create a certain atmosphere of the outdoors.

How do you do that?

On the one hand, by incorporating into my architecture green, i.e. living, organic matter. In my “House with Plants” for a young Tokyo family, for example, I placed clods of earth in the middle of the living room and created a forest floor with bushes and trees on this. On the other hand, I use inorganic building blocks from nature and adjust these or use them as architectural readymades.

You will have to explain further!

In Dari, in south-west China, I am currently planning a coherent ensemble of eight weekend cottages with a total area of around 4,000 square metres. Nature in this truly impressive landscape consists of large, round stones, and boulders, some three to four metres high, that are scattered in the forest. I use these boulders for example as supports and pillars for a concrete roof that will float over them. The stones are neither moved in position nor worked, but used just as we find them. The building is then simply glazed all around. That’s it.

Is glass an important building material for you?

Yes, I use a lot of glass, because it possesses numerous advantages that other building materials do not have. But glass is no more important than wood, brick, steel or concrete. It is simply different.

The restaurant that you are currently building in Yamaguchi is also highly archaic in style.

Yes, it is a little French restaurant that has some of the feel of an artificially created cave system. I got the construction workers to dig holes directly on the site, into which we then placed reinforcement cages, then filled them with concrete. In this way we used the soil as formwork. Finally, the soil underneath and to the side was removed and the entire structure given all-round glazing. I really like this project, because here the underground natural world lives on as a positive impression in concrete. The structure of the soil can still clearly be seen in the surface of the concrete.

What did the clients say to these unusual notions?

I hope they really like them! I think we have to constantly develop our understanding of architecture, because cities are changing – and with them the living conditions and creative possibilities. The more nature is pushed back, the more we have to be careful to create a certain natural atmosphere. That’s what I stand for with my architecture.

Many architects – especially in Japan – respond to this change in circumstances with maximum transparency. The result is often fully glazed buildings, such as the House Na by Sou Fujimoto.

A fantastic house! These are exciting ideas that work with the total dissolving of the boundaries between inside and outside, private and public sphere. I personally find this concept too hard. I prefer a gentle, multi-layered transition, such as we know from our own architectural history. This does not mean that we are obliged to use rice paper walls. We can also work with light, with spatial depth, with deliberately staged views and silhouettes...

...or even with underground caves.

You said it! The most important building block in architecture and urban planning is diversity. We live in a century of density. Cities are getting ever bigger and more densely populated. Our job is to manage this development intelligently. There are so many different concepts for this. I focus on mine.

The architect as designer – not merely of houses, but above all of society?

I want my kind of architecture to contribute, at least minimally, to the improvement and enrichment of the world. I want with my projects to create a small world on a large scale. I want to enlarge the world.

Junya Ishigami, born in 1974 in Kanagawa prefecture. He studied architecture at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. From 2000 to 2004 he worked for the architectural firm of SANAA. In 2004 he founded his own firm, junya.ishigami + associates. In 2008 and 2010, he participated in the Venice Biennale of Architecture and was awarded the Golden Lion for his contribution. Since 2010 he has been Associate Professor at Tohoku University in Japan and, since 2014, guest critic at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, USA.

Creative even without windows: Junya Ishigami in his studio, opened in Tokyo in 2004 in the basement of a former nightclub.

Clear structures: model for the “Home for the Elderly” for the Japanese city of Tohoku.

Underground: the cave-like restaurant and dwelling in Yamaguchi.

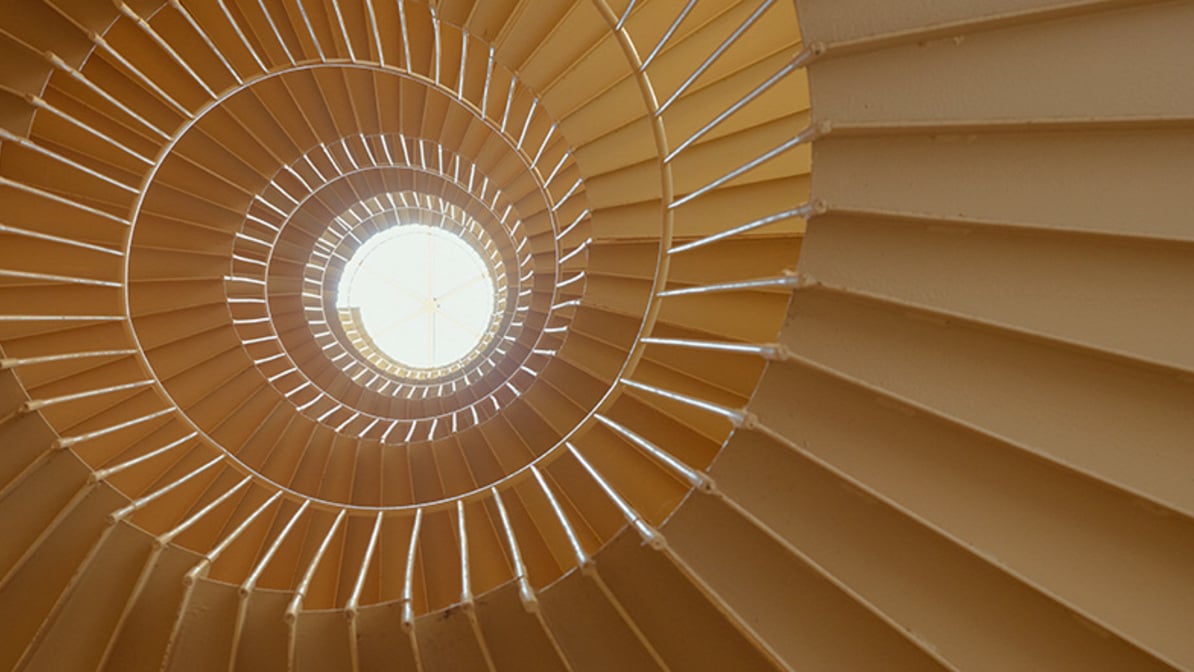

Nature as an inspiration: the roof of the Kanagawa Institute of Technology (2008) rests on 305 pillars, all of which have a slightly different orientation – like trees in a forest.

The outside is inside: trees grow in Ishigami’s “House with Plants” in Tokyo (2012).

Still want more?

See here for further interesting reading matter.