Reframe Your Point of View.

Keep the outside, outside.

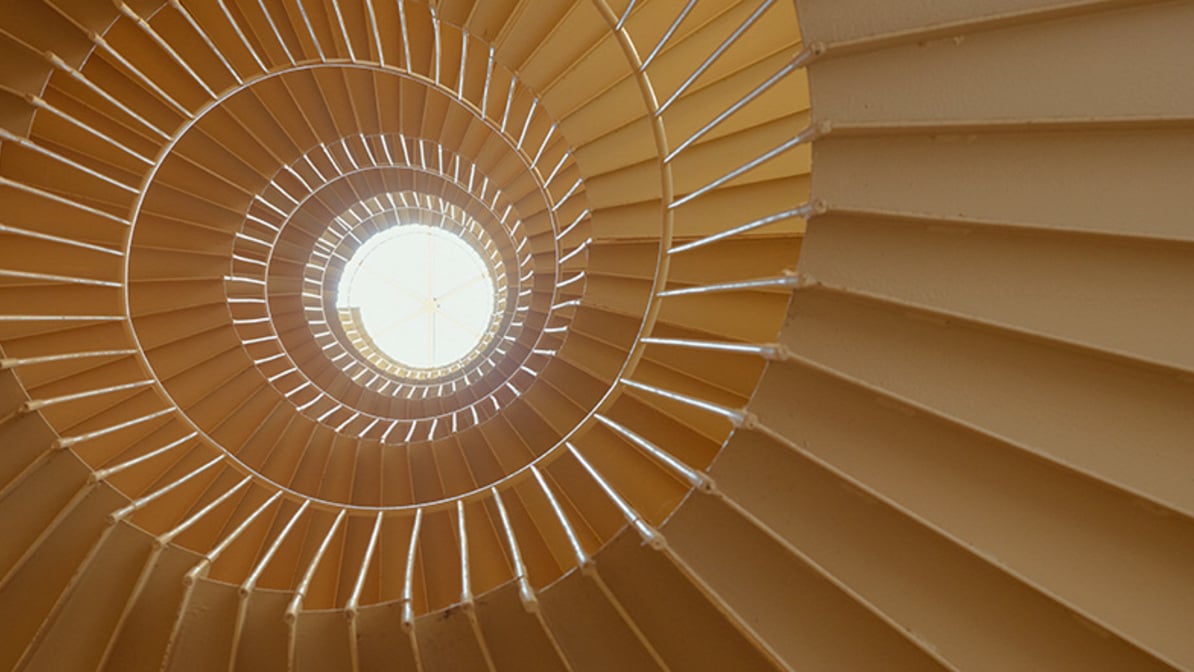

Outside? A world of uproar. The tyranny of reality. Nature taking its course. It’s all too loud, too excessive, too explicit. For Rinus Van de Velde, at least. He prefers to concentrate on his work inside, protected. Behind thick walls. Ensconced inside, that’s where his stories emerge, stories that tell of the wide world out there while also creating a fantastical parallel universe. His art becomes an interface that plays with overlaps. Kersten Geers took the Belgian artist and his approach seriously. With his architectural practice OFFICE he created a retreat for the artist which experiments with the absence of light and which itself becomes a narrative; a single window brings light to the first-floor artist’s workshop, framing the wild profusion of nature like a painting. For the artist at work, it transforms reality into an abstracted quotation. Viewed from outside, the building offers a paradox: present, yet absent. A site visit with multiple perspectives on the outskirts of the small Belgian city of Leuven.

Rinus van de Velde and Kersten Geers in conversation with Julia Christian

Photos: Charlie de Keersmaeker

Rinus Van de Velde, you design spaces out of styrofoam and cardboard. Your alter egos – in charcoal drawings, in life-sized ceramics, or in films – experience all kinds of adventures: walking through the desert with a briefcase or alone in the forest with a suckling pig over a campfire. What links your media and your materials?

RVdV: I tell stories. I started with charcoal drawings. Back then, when I was 20, I wanted to master a real discipline and find freedom within that restriction. But after ten years it became super boring, and I had still only mastered charcoal drawing to a certain degree. Then I became a father and more self-assured. As a young artist it was hard for me to believe that a ceramic ashtray can be art. After 20 years in the art world I thought: I’m just going to go for it, I feel like it. So I discovered a lot of other media. But the basic idea stayed the same: I pretend I’m living another life.

Is this another one of your stories: having a house built on the edge of a housing estate in a small Belgian city, but actually living in Antwerp?

RVdV: For a long time I’ve wanted a “country house”. I find forests and real nature too wild and dangerous. I grew up here in Leuven. So I took my drawings to OFFICE. I was thinking about lots of glass, a modern building, and then Kersten said …

KG: Far too banal!

RVdV: Instead he suggested framing this overgrown plot at the back with a window, to turn nature into an artwork. He convinced me on the spot.

KG: Well, he wanted a country house. So it was consistent. And the outside was meant to stay outside. Because above all it was supposed to be a retreat.

From a modern glass building to a workshop with just one window – you’ll have to explain!

RVdV: I don’t need daylight to paint. I’m not an Impressionist. This whole discussion about northern light is superfluous. Every artwork has a different impact depending on its setting. Is there northern light in an apartment or a collection? Probably not. And artificial light is fantastic these days!

But light, or the absence of light, plays an utterly central role in your art.

RVdV: In compositional terms, yes. And also the way it has been used in art history. But when I work in the workshop it doesn’t matter.

KG: Rinus’s conception of a workshop is in effect an “anti-studio”. When I listen to him, I notice that in architecture everything often comes together at a certain point and suddenly makes sense. Perhaps that is its beauty, and the beauty of art – we value architecture and art for similar or differing reasons, but both express shared values in ambiguous ways. You don’t have step into someone else’s head to understand them. But sometimes you only understand why it makes sense for the other person when they talk about it.

Does that mean there are two perspectives in planning and construction processes that come together at some point? So it’s neither personal expression nor contract work, but always neither one of them – and both at the same time?

KG: Architecture per se is not complicated. Its complexity is part of its nature, yet it has its origin in clear principles. I think OFFICE is completely misunderstood: “Oh those lads are SO abstract, and everything is always geometric.” The important thing is: the structure has to be authentic. Real. There’s nothing worse than standing somewhere and thinking: which idiot did this? What on earth was the architect thinking here? And over there? Instead you should immediately have the sense that it all makes sense.

Rinus van de Velde and Kersten Geers in conversation with Julia Christian

Photos: Charlie de Keersmaeker

Rinus Van de Velde, you design spaces out of styrofoam and cardboard. Your alter egos – in charcoal drawings, in life-sized ceramics, or in films – experience all kinds of adventures: walking through the desert with a briefcase or alone in the forest with a suckling pig over a campfire. What links your media and your materials?

RVdV: I tell stories. I started with charcoal drawings. Back then, when I was 20, I wanted to master a real discipline and find freedom within that restriction. But after ten years it became super boring, and I had still only mastered charcoal drawing to a certain degree. Then I became a father and more self-assured. As a young artist it was hard for me to believe that a ceramic ashtray can be art. After 20 years in the art world I thought: I’m just going to go for it, I feel like it. So I discovered a lot of other media. But the basic idea stayed the same: I pretend I’m living another life.

Is this another one of your stories: having a house built on the edge of a housing estate in a small Belgian city, but actually living in Antwerp?

RVdV: For a long time I’ve wanted a “country house”. I find forests and real nature too wild and dangerous. I grew up here in Leuven. So I took my drawings to OFFICE. I was thinking about lots of glass, a modern building, and then Kersten said …

KG: Far too banal!

RVdV: Instead he suggested framing this overgrown plot at the back with a window, to turn nature into an artwork. He convinced me on the spot.

KG: Well, he wanted a country house. So it was consistent. And the outside was meant to stay outside. Because above all it was supposed to be a retreat.

From a modern glass building to a workshop with just one window – you’ll have to explain!

RVdV: I don’t need daylight to paint. I’m not an Impressionist. This whole discussion about northern light is superfluous. Every artwork has a different impact depending on its setting. Is there northern light in an apartment or a collection? Probably not. And artificial light is fantastic these days!

But light, or the absence of light, plays an utterly central role in your art.

RVdV: In compositional terms, yes. And also the way it has been used in art history. But when I work in the workshop it doesn’t matter.

KG: Rinus’s conception of a workshop is in effect an “anti-studio”. When I listen to him, I notice that in architecture everything often comes together at a certain point and suddenly makes sense. Perhaps that is its beauty, and the beauty of art – we value architecture and art for similar or differing reasons, but both express shared values in ambiguous ways. You don’t have step into someone else’s head to understand them. But sometimes you only understand why it makes sense for the other person when they talk about it.

Does that mean there are two perspectives in planning and construction processes that come together at some point? So it’s neither personal expression nor contract work, but always neither one of them – and both at the same time?

KG: Architecture per se is not complicated. Its complexity is part of its nature, yet it has its origin in clear principles. I think OFFICE is completely misunderstood: “Oh those lads are SO abstract, and everything is always geometric.” The important thing is: the structure has to be authentic. Real. There’s nothing worse than standing somewhere and thinking: which idiot did this? What on earth was the architect thinking here? And over there? Instead you should immediately have the sense that it all makes sense.

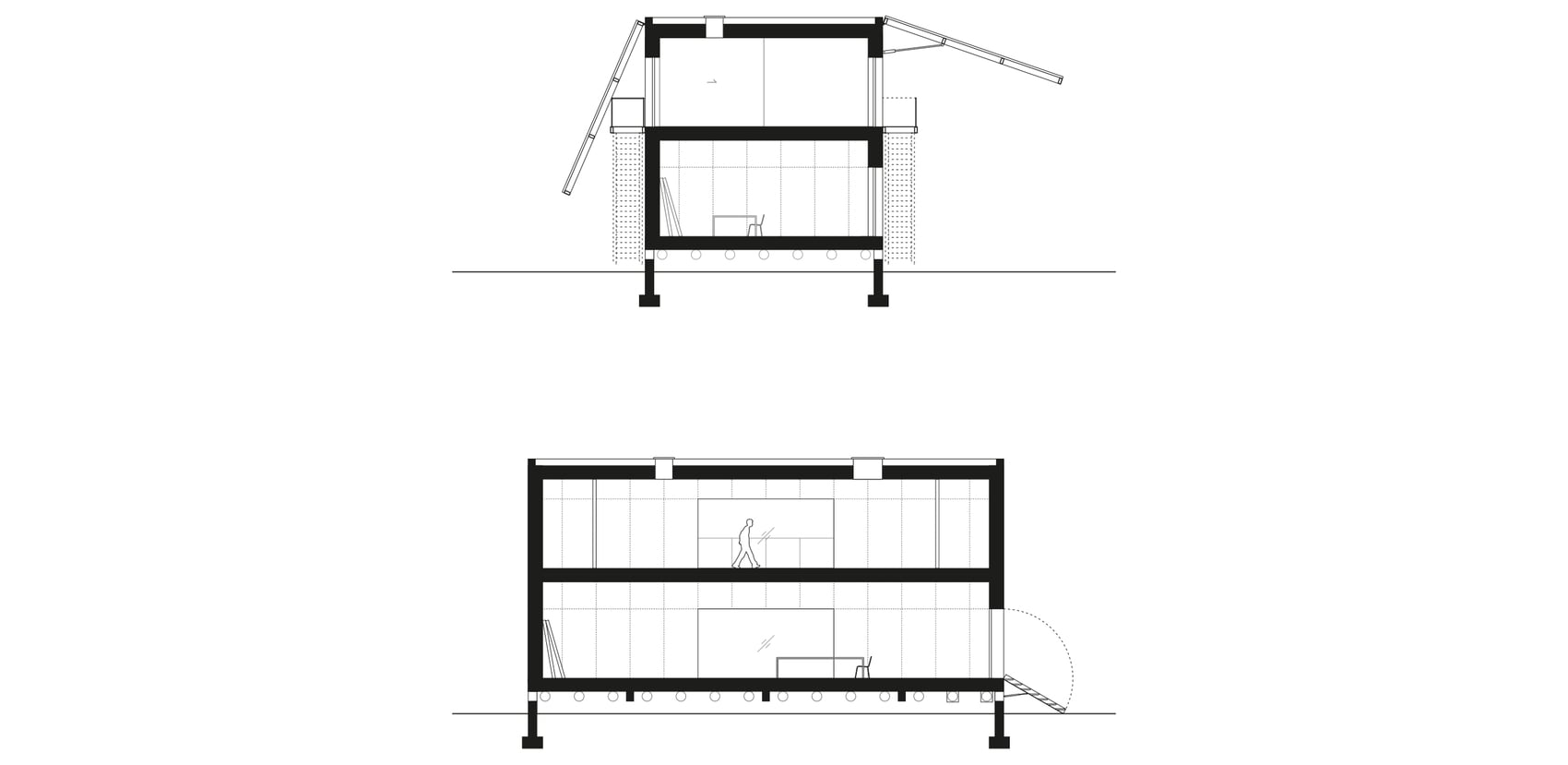

An artistic Noah’s Art: conceived as a plain concrete box, the artist’s workshop is in a flood-prone area on the edge of Leuven. Round perforations in the lower façade enable controlled flooding of a crawl space beneath the ground floor.

Rinus Van de Velde (left) and Kersten Geers (right) in conversation with Julia Christian

OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen is a Brussels-based architectural practice, established in 2002 by Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, which brings together theory and practice. OFFICE combines pragmatic design with rapid decision-making processes and sees architecture as a civil obligation. In parallel with the practice, the founders head up design studios at institutions such as the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio and the Harvard Graduate School of Design. OFFICE has a team of around 40 architects and is structured as a partnership.

Light and calm: the living space on the upper floor is designed as a creative retreat for the Antwerp-based artist. Two sliding doors of equal size on both sides let in daylight.

One house, no windows: Van de Velde appends his longings and anxieties in handwriting, anchoring the work in a larger narrative and determining its place. Rinus Van de Velde “No, no, no windows, …”, 2021, oil pastels on canvas, 110 x 67.5 cm, courtesy of Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

So that means form follows function?

KG: No, I wouldn’t use that word. Functionality is a leftover from the ’20s – the kitchen this wide, the door on the right-hand side. I’m talking about a return to an ancient idea of architecture: an ordering of spaces. Spaces have a certain height, windows have a certain proportion, and you enter the space from outside. Whether you place the sofa here or the area that was once conceived as a living space is now an office is irrelevant. Good architecture ensures that people feel comfortable in a space.

And protected?

KG: I think you always establish a relationship to a place. Sometimes it’s a strange kind of protection; the house we built in Spain only had a roof, no walls, but there was so much wild growth around it that you were alone. And here, for example, at first glance it doesn’t seem at all like there’s a relationship with this piece of land.

But doesn’t art need to be in dialogue with the world?

RVdV: I recently read a book by Werner Herzog. He writes: “Look at the sky, even the stars are chaotic.” This world doesn’t inspire me much. That’s why I didn’t want big windows or a connection to the outside world. Many of my artworks depict windowless houses. Of course I live here, reality creeps in, but as an artist I don’t react politically to the outside world. I create from books and my imagination. I find inspiration when I’m in my studio apartment and I sit and think. For me, being a true artist means always being alone. You create your own universe.

KG: We wanted to take this idea seriously and not satirise it. That’s why there are stairs hanging on the outside of the house. If you raise them, there’s no access: it’s like a drawbridge. Two canopies, one fixed and one mobile, provide privacy and covered outdoor areas. And the building looks like an unfolding cardboard box –a motif and material that Rinus uses often. The workshop and the studio apartment are not connected.

RVdV: Stairs would have been a waste of space! I prefer to use the space for hanging out and arranging my work. I like that the workshop is a public space, separated from my private domain.

KG: The rear part of the plot will be a public garden. Together with the workshop on the lower floor, it indicates that the building also has a social function and that it’s not just someone living out his architectural fantasy. Particularly as it’s in a flood zone.

Are you allowed to build in flood-prone areas?

KG: That’s why the workshop starts at a height of 1.20 metres. Below it is a hollow space with a perforated façade that allows water to flow through the building. You could say that with this and the “drawbridge”, the construction resembles a Noah’s Ark.

A Noah’s Ark as a retreat from the world … Do you need solitude to live out your numerous artistic double lives?

RVdV: One of my exhibitions, inspired by Joseph Cornell, was called “Armchair Voyager”. Cornell lived in New York and he never left the house that he shared with his mother. In the cellar he built little wooden boxes and created tiny universes in them. The armchair voyager who sits on his sofa and goes on the most incredible voyages – that sounds like a good life to me.

“Perhaps that is the beauty of architecture and art: they are valued for similar or differing reasons, but both express shared values in ambiguous ways.“ – Kersten Geers

Do your alter egos go on adventures on your behalf?

RVdV: There used to just be one alter ego who experienced a chapter of his life in each exhibition. I had all these little notebooks and I had to remember: right now I am this old, I have a dog called XY. But I wanted to travel freely in space and time. So I threw all that out and told myself: from now on, anything is possible. I can be a chess player, I can play tennis, I can be a friend of Claude Monet. And I can fail, I can be an anti-hero. It’s so liberating, there’s no pressure. I think imagining you’re someone who you’re not is deeply human. Children do it all the time. The fact that humans can daydream and fantasise is a gift, because you can experience more in your mind than you can in reality.

Don’t we spend too much time in our own minds? Shouldn’t we be concentrating on gathering more sensory impressions?

RVdV: When I was 14 I went with my parents to the Grand Canyon. It took forever, and when we got there I announced: “I’m not getting out!” I was an annoying teenager, that’s probably how I coped. I never saw the Grand Canyon and it was only later that I discovered it through David Hockney’s images. I swear: no one depicts it better. In reality I would probably have just thought: “That’s it?” There is so much good documentation, paintings and books – why do I have to go there?

A few years ago I was in Dallas, at the site where John F. Kennedy was shot. You stand there and you wonder what you’re supposed to feel. I would rather watch a documentary and have enough space to think about how the attack changed the world. Perhaps it’s different for people who like travelling …

“The fact that humans can daydream and fantasise is a gift, because you can experience more in your mind than you can in reality.” – Rinus Van De Velde

You don’t like travelling?

RVdV: No, for me the world is too chaotic and reality is full of obstacles. I can’t enjoy the process. It’s very practical that staying at home is also more sustainable.

Does your architecture respond to climate change?

KG: I would be lying if I said “yes”. We have to vote for the right party, travel by bicycle, walk instead of using the car for the most ridiculous journeys. We shouldn’t be piling up rubbish unnecessarily – that is our contribution to fighting climate change. And yes, ideally you should be able to use a building for a very long time.

For ten years we’ve been working on the media campus for Radio Television Schweiz in Lausanne. Students who see our architecture are disappointed. They say: “Hmm, that is a building for radio and television.” And I think: “Yes! Is that a problem?” In Antwerp we transformed an old abattoir into a school, and everyone was excited about this “recycling”. (laughs) I am the architect of both buildings, and both of them are responsible.

But if we start believing in the cliché of “good behaviour”, we lose sight of ourselves and kill culture. You’re just replacing everything with gestures. Before you know it, Rinus isn’t allowed to paint on canvas any more because it uses too many resources. I doubt that’s going to save the world. As an architect you have a public role: what does a building say to the people who walk past it? That is responsibility. It’s a small context, but it’s precise.

“Kersten suggested framing this overgrown plot at the back with a window, to turn nature into an artwork. He convinced me on the spot.” – Rinus Van De Velde

Is there a point at which art and architecture come into contact, beyond museums and artists' workshops?

KG: Architecture is essentially about “framing”. There is an inside and an outside, and perhaps it is in the transition that the essential transpires. Personally I have always been obsessed with painting, with the way a canvas creates a world. Piero della Francesca, Ed Ruscha or Rinus – they’re all different, but they all depict an inside and an outside. In architecture you differentiate, although in a much more simplified, slightly clichéd way, between pictorial and sculptural approaches. Donato Bramante is pictorial, Michelangelo is sculptural. And I think we have always leaned toward painting because our buildings are very simple and focused on visual relationships. Complexity of form has never been particularly important.

RVdV: You create hierarchies on the canvas, too.

KG: Exactly! What will be on the left, on the right, what’s up front and how deep is the space? In both disciplines you’re looking for relationships, framing, addressing the exterior and the interior, organising spaces. That’s why I’m so happy about this project, because there’s this one moment in which you come into contact. With no pretension at all. Not because the building is supposed to represent Rinus’s work. In the end it’s a house, and that’s fine, as long as he feels good in it.

KG: No, I wouldn’t use that word. Functionality is a leftover from the ’20s – the kitchen this wide, the door on the right-hand side. I’m talking about a return to an ancient idea of architecture: an ordering of spaces. Spaces have a certain height, windows have a certain proportion, and you enter the space from outside. Whether you place the sofa here or the area that was once conceived as a living space is now an office is irrelevant. Good architecture ensures that people feel comfortable in a space.

And protected?

KG: I think you always establish a relationship to a place. Sometimes it’s a strange kind of protection; the house we built in Spain only had a roof, no walls, but there was so much wild growth around it that you were alone. And here, for example, at first glance it doesn’t seem at all like there’s a relationship with this piece of land.

But doesn’t art need to be in dialogue with the world?

RVdV: I recently read a book by Werner Herzog. He writes: “Look at the sky, even the stars are chaotic.” This world doesn’t inspire me much. That’s why I didn’t want big windows or a connection to the outside world. Many of my artworks depict windowless houses. Of course I live here, reality creeps in, but as an artist I don’t react politically to the outside world. I create from books and my imagination. I find inspiration when I’m in my studio apartment and I sit and think. For me, being a true artist means always being alone. You create your own universe.

KG: We wanted to take this idea seriously and not satirise it. That’s why there are stairs hanging on the outside of the house. If you raise them, there’s no access: it’s like a drawbridge. Two canopies, one fixed and one mobile, provide privacy and covered outdoor areas. And the building looks like an unfolding cardboard box –a motif and material that Rinus uses often. The workshop and the studio apartment are not connected.

RVdV: Stairs would have been a waste of space! I prefer to use the space for hanging out and arranging my work. I like that the workshop is a public space, separated from my private domain.

KG: The rear part of the plot will be a public garden. Together with the workshop on the lower floor, it indicates that the building also has a social function and that it’s not just someone living out his architectural fantasy. Particularly as it’s in a flood zone.

Are you allowed to build in flood-prone areas?

KG: That’s why the workshop starts at a height of 1.20 metres. Below it is a hollow space with a perforated façade that allows water to flow through the building. You could say that with this and the “drawbridge”, the construction resembles a Noah’s Ark.

A Noah’s Ark as a retreat from the world … Do you need solitude to live out your numerous artistic double lives?

RVdV: One of my exhibitions, inspired by Joseph Cornell, was called “Armchair Voyager”. Cornell lived in New York and he never left the house that he shared with his mother. In the cellar he built little wooden boxes and created tiny universes in them. The armchair voyager who sits on his sofa and goes on the most incredible voyages – that sounds like a good life to me.

“Perhaps that is the beauty of architecture and art: they are valued for similar or differing reasons, but both express shared values in ambiguous ways.“ – Kersten Geers

Do your alter egos go on adventures on your behalf?

RVdV: There used to just be one alter ego who experienced a chapter of his life in each exhibition. I had all these little notebooks and I had to remember: right now I am this old, I have a dog called XY. But I wanted to travel freely in space and time. So I threw all that out and told myself: from now on, anything is possible. I can be a chess player, I can play tennis, I can be a friend of Claude Monet. And I can fail, I can be an anti-hero. It’s so liberating, there’s no pressure. I think imagining you’re someone who you’re not is deeply human. Children do it all the time. The fact that humans can daydream and fantasise is a gift, because you can experience more in your mind than you can in reality.

Don’t we spend too much time in our own minds? Shouldn’t we be concentrating on gathering more sensory impressions?

RVdV: When I was 14 I went with my parents to the Grand Canyon. It took forever, and when we got there I announced: “I’m not getting out!” I was an annoying teenager, that’s probably how I coped. I never saw the Grand Canyon and it was only later that I discovered it through David Hockney’s images. I swear: no one depicts it better. In reality I would probably have just thought: “That’s it?” There is so much good documentation, paintings and books – why do I have to go there?

A few years ago I was in Dallas, at the site where John F. Kennedy was shot. You stand there and you wonder what you’re supposed to feel. I would rather watch a documentary and have enough space to think about how the attack changed the world. Perhaps it’s different for people who like travelling …

“The fact that humans can daydream and fantasise is a gift, because you can experience more in your mind than you can in reality.” – Rinus Van De Velde

You don’t like travelling?

RVdV: No, for me the world is too chaotic and reality is full of obstacles. I can’t enjoy the process. It’s very practical that staying at home is also more sustainable.

Does your architecture respond to climate change?

KG: I would be lying if I said “yes”. We have to vote for the right party, travel by bicycle, walk instead of using the car for the most ridiculous journeys. We shouldn’t be piling up rubbish unnecessarily – that is our contribution to fighting climate change. And yes, ideally you should be able to use a building for a very long time.

For ten years we’ve been working on the media campus for Radio Television Schweiz in Lausanne. Students who see our architecture are disappointed. They say: “Hmm, that is a building for radio and television.” And I think: “Yes! Is that a problem?” In Antwerp we transformed an old abattoir into a school, and everyone was excited about this “recycling”. (laughs) I am the architect of both buildings, and both of them are responsible.

But if we start believing in the cliché of “good behaviour”, we lose sight of ourselves and kill culture. You’re just replacing everything with gestures. Before you know it, Rinus isn’t allowed to paint on canvas any more because it uses too many resources. I doubt that’s going to save the world. As an architect you have a public role: what does a building say to the people who walk past it? That is responsibility. It’s a small context, but it’s precise.

“Kersten suggested framing this overgrown plot at the back with a window, to turn nature into an artwork. He convinced me on the spot.” – Rinus Van De Velde

Is there a point at which art and architecture come into contact, beyond museums and artists' workshops?

KG: Architecture is essentially about “framing”. There is an inside and an outside, and perhaps it is in the transition that the essential transpires. Personally I have always been obsessed with painting, with the way a canvas creates a world. Piero della Francesca, Ed Ruscha or Rinus – they’re all different, but they all depict an inside and an outside. In architecture you differentiate, although in a much more simplified, slightly clichéd way, between pictorial and sculptural approaches. Donato Bramante is pictorial, Michelangelo is sculptural. And I think we have always leaned toward painting because our buildings are very simple and focused on visual relationships. Complexity of form has never been particularly important.

RVdV: You create hierarchies on the canvas, too.

KG: Exactly! What will be on the left, on the right, what’s up front and how deep is the space? In both disciplines you’re looking for relationships, framing, addressing the exterior and the interior, organising spaces. That’s why I’m so happy about this project, because there’s this one moment in which you come into contact. With no pretension at all. Not because the building is supposed to represent Rinus’s work. In the end it’s a house, and that’s fine, as long as he feels good in it.

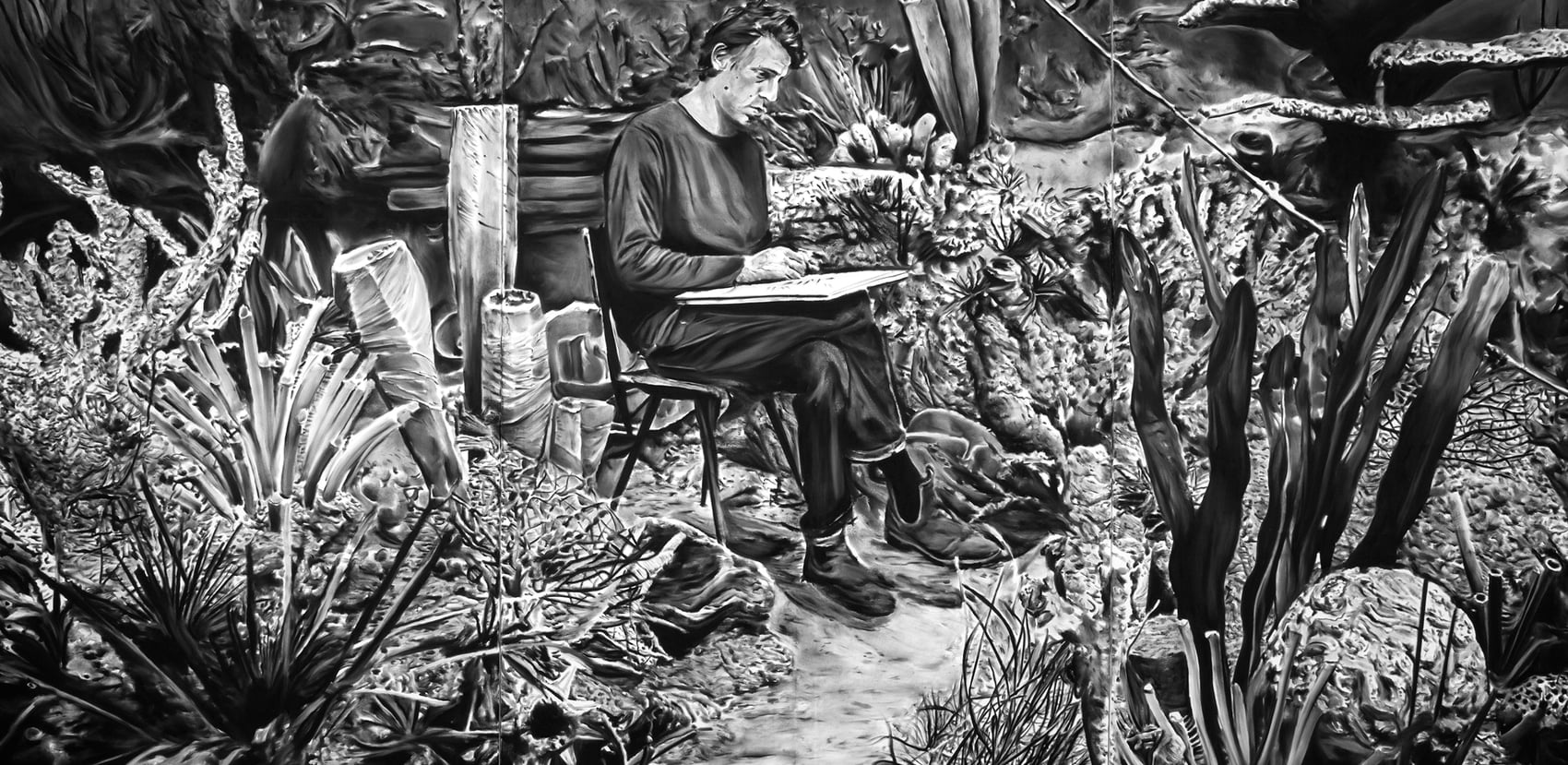

Truth and illusion, reality and fantasy: Van de Velde paints Van de Velde as a plein air painter, although he only traverses his numerous realities in his mind. Rinus Van de Velde “The principle impulse …”, 2021, charcoal on canvas, 300 x 525 cm, courtesy of Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Building and landscape: the window puts the surrounding overgrowth on display like an artwork – a conscious contrast to the monolithic concrete architecture that enables retreat and concentration.

“Paul modelling in the air”, Siberian charcoal on paper, 200 × 240 cm, Sammlung Finstral (acquired 2014) is a portrait of the sculptor Paul Schelling, whose influence Van de Velde describes as “pivotal”: “Paul modelled as though he were designing reality itself. He was like a god, tirelessly creating his own universe. His impossible life’s work was to create a sculpture of everything that exists. A male and female human, every type of mammal, reptile, insect, bird, water, mountains, the planet itself. Naturally it drove him mad. No one around him ever heard him speaking. He lived in his own universe, forever static and incomplete.”

Modern fortress: the aluminium canopies of the flat roof, one movable, one fixed, offer privacy as well as a covered outdoor area. Work and living space are accessible via a retractable outdoor staircase, a contrast to the static concrete volumes.

Still want more?

See here for further interesting reading matter.