Glass meets window.

Paris comes to Gochsheim. Fabrice Didier of Saint-Gobain visits the Finstral glassworks in Lower Franconia.

It is a truism that a window needs glass to become a window. But when a glass producer with 350 years of history behind it meets a passionate window manufacturer, things are suddenly different: Saint-Gobain’s Fabrice Didier and Finstral’s Florian Oberrauch talk about light and life, about solar irradiation and Louis XIV, about innovation, lightness and perseverance. And about glass, of course. And windows. Portrait of an encounter.

If we understand architecture as a language that creates very different narratives according to its context, then windows must also change depending upon their context. Box-type windows, for example, do not recount the story of democratic transparency, while large glass surfaces do not necessarily accord with the history of a 500-year-old Swiss farm located in a mountain landscape. This in turn means that architects as storytellers can draw on a very wide choice – of window material that in its turn consists of a vast range of window and sash frames... and glass. Upon what exactly does this connection depend? To answer this question, a glass expert from Paris met a window expert from Unterinn on South Tyrol’s Ritten mountain: Fabrice Didier, vice-president of the Saint-Gobain group, is responsible for marketing and was previously responsible for the company’s glass business in Germany. Florian Oberrauch, a nephew of Finstral founder Hans Oberrauch, sits on the board of directors and is responsible for production and logistics.

The venue is Lower Franconia. Didier and Oberrauch meet at the Finstral insulation glass factory in Gochsheim, right in the middle of this German province, in an industrial area that was once green fields: easily accessible, but only by motorway. First of all, our host André Mehlhorn, member of the management board of Finstral Deutschland, leads us into the meeting room on the second floor before inviting us on a tour of the factory building. Up here we are of course sitting behind Finstral windows and therefore behind glass made by Saint- Gobain – as, for the past four years, Europe’s most highly certified window manufacturer has exclusively been using panes from Europe’s leading flat glass producer. It is a hot day and, despite the solar control glass, the ventilation is working flat out. Later, when the talk turns to glass as a vector of innovation, Florian Oberrauch states “We cannot be satisfied with this – things have to be better in energy terms.” He agrees with Fabrice Didier that this has to happen – and soon. But before we look ahead to smart windows that can adapt to the time of day and the season, we look back. How did the story of French glass, which has made window history, actually begin? And where?

It all began – as with so much in modern France - with Louis XIV who, on the one hand, caused both his court and absolutism to shine in Europe – but who was on the other much less narcissistic than the pomp and splendour of the Palace of Versailles might suggest. Fabrice Didier leans forward and his voice softens. You can tell that he knows very well how much his company owes to the “Sun King”. “When Louis XIV designed Versailles,” explains Didier, “his aim was not simply to build a memorial to himself. His main concern was to promote the most innovative technologies of the day, bringing them together in one place and thus making them visible.” Louis’s vision of completely new water features required completely new types of pump. While for the famous Hall of Mirrors he needed mirror glass that had never before existed in this form and size. “The idea was that more light should enter the rooms, so that not so many candles had to be lit in the early afternoon. They created large amounts of smoke.”

In 1665 Louis’s Minister of Finance, Colbert, was tasked with founding a mirror glass factory: the origin of the company that later became Saint-Gobain. Didier calls the first location in Paris a “pilot plant”. But, as is so often the case, the beginning was difficult. “In the first year it was planned to produce 1,000 glass plates”, says Fabrice Didier. “But, of the 1,000 pieces, 999 broke. The new factory itself immediately went bankrupt. But then the engineer responsible marched out to Versailles and said, Wait a moment. One plate has survived, which shows that the production parameters were not constant. If we can understand these parameters better, we can turn one plate into ten, then a hundred, then a thousand.” Colbert was convinced and continued with the financing. The engineer discovered that the surface upon which the cylindrically blown glass was cut, rolled flat and allowed to cool should not itself be cold. The temperature difference was otherwise simply too great: the glass would break. So they warmed the table and, some time later, invented the revolutionary table rolling process, whereby the melted glass is poured and rolled directly on the hot table. Shortly thereafter the factory moved to Picardy in northern France, to the village of Saint-Gobain after which the company is named. This was in 1692. “From that moment on, we have known success”, says Fabrice Didier, pausing for a moment. “I still tell this story today, preferably to our staff in the research department. I want to show them that sometimes you have to persevere. Then as now.” In 1993, after 301 years, Saint-Gobain closed its plant in Saint-Gobain; the company headquarters, long located in Paris, are now being rebuilt – using plenty of glass, of course. The spirit of the early days can still be felt today. “It makes us proud that Saint-Gobain has for the last seven years been voted among the world’s 100 most innovative companies,” says Fabrice Didier. “Always think ahead, trying out new things and pushing forward... You can say that this attitude is part of our genetic make-up.”

If we understand architecture as a language that creates very different narratives according to its context, then windows must also change depending upon their context. Box-type windows, for example, do not recount the story of democratic transparency, while large glass surfaces do not necessarily accord with the history of a 500-year-old Swiss farm located in a mountain landscape. This in turn means that architects as storytellers can draw on a very wide choice – of window material that in its turn consists of a vast range of window and sash frames... and glass. Upon what exactly does this connection depend? To answer this question, a glass expert from Paris met a window expert from Unterinn on South Tyrol’s Ritten mountain: Fabrice Didier, vice-president of the Saint-Gobain group, is responsible for marketing and was previously responsible for the company’s glass business in Germany. Florian Oberrauch, a nephew of Finstral founder Hans Oberrauch, sits on the board of directors and is responsible for production and logistics.

The venue is Lower Franconia. Didier and Oberrauch meet at the Finstral insulation glass factory in Gochsheim, right in the middle of this German province, in an industrial area that was once green fields: easily accessible, but only by motorway. First of all, our host André Mehlhorn, member of the management board of Finstral Deutschland, leads us into the meeting room on the second floor before inviting us on a tour of the factory building. Up here we are of course sitting behind Finstral windows and therefore behind glass made by Saint- Gobain – as, for the past four years, Europe’s most highly certified window manufacturer has exclusively been using panes from Europe’s leading flat glass producer. It is a hot day and, despite the solar control glass, the ventilation is working flat out. Later, when the talk turns to glass as a vector of innovation, Florian Oberrauch states “We cannot be satisfied with this – things have to be better in energy terms.” He agrees with Fabrice Didier that this has to happen – and soon. But before we look ahead to smart windows that can adapt to the time of day and the season, we look back. How did the story of French glass, which has made window history, actually begin? And where?

It all began – as with so much in modern France - with Louis XIV who, on the one hand, caused both his court and absolutism to shine in Europe – but who was on the other much less narcissistic than the pomp and splendour of the Palace of Versailles might suggest. Fabrice Didier leans forward and his voice softens. You can tell that he knows very well how much his company owes to the “Sun King”. “When Louis XIV designed Versailles,” explains Didier, “his aim was not simply to build a memorial to himself. His main concern was to promote the most innovative technologies of the day, bringing them together in one place and thus making them visible.” Louis’s vision of completely new water features required completely new types of pump. While for the famous Hall of Mirrors he needed mirror glass that had never before existed in this form and size. “The idea was that more light should enter the rooms, so that not so many candles had to be lit in the early afternoon. They created large amounts of smoke.”

In 1665 Louis’s Minister of Finance, Colbert, was tasked with founding a mirror glass factory: the origin of the company that later became Saint-Gobain. Didier calls the first location in Paris a “pilot plant”. But, as is so often the case, the beginning was difficult. “In the first year it was planned to produce 1,000 glass plates”, says Fabrice Didier. “But, of the 1,000 pieces, 999 broke. The new factory itself immediately went bankrupt. But then the engineer responsible marched out to Versailles and said, Wait a moment. One plate has survived, which shows that the production parameters were not constant. If we can understand these parameters better, we can turn one plate into ten, then a hundred, then a thousand.” Colbert was convinced and continued with the financing. The engineer discovered that the surface upon which the cylindrically blown glass was cut, rolled flat and allowed to cool should not itself be cold. The temperature difference was otherwise simply too great: the glass would break. So they warmed the table and, some time later, invented the revolutionary table rolling process, whereby the melted glass is poured and rolled directly on the hot table. Shortly thereafter the factory moved to Picardy in northern France, to the village of Saint-Gobain after which the company is named. This was in 1692. “From that moment on, we have known success”, says Fabrice Didier, pausing for a moment. “I still tell this story today, preferably to our staff in the research department. I want to show them that sometimes you have to persevere. Then as now.” In 1993, after 301 years, Saint-Gobain closed its plant in Saint-Gobain; the company headquarters, long located in Paris, are now being rebuilt – using plenty of glass, of course. The spirit of the early days can still be felt today. “It makes us proud that Saint-Gobain has for the last seven years been voted among the world’s 100 most innovative companies,” says Fabrice Didier. “Always think ahead, trying out new things and pushing forward... You can say that this attitude is part of our genetic make-up.”

Conversation between glass and window enthusiasts: Fabrice Didier (left) and Florian Oberrauch.

Now it is Florian Oberrauch’s turn to speak. Ultimately Finstral too cannot simply remain static. There are good reasons for Saint-Gobain being selected as a supplier in 2015: the continued design and development of windows requires just the right glass. “It’s been five years since Saint-Gobain came to us here on the Ritten with their plans for revolutionary triple glazing that can offer extremely good insulation while still letting in just as much natural light as double glazing. It was still a secret at the time. We were immediately delighted and wanted to share in this innovative idea. We have also actively requested manufacturing from Saint-Gobain. Once the glass was available, we added it to our programme as a new Finstral standard, with the name Max-Valor.” Oberrauch does not say so, but the idea is obvious: will Finstral play a similar role for Saint-Gobain in our time as Louis XIV in the 17th century as its first customer, a significant buyer and inspiration for its products? Fabrice Didier responds indirectly when he confidently emphasises: “We want to work with those who are the most successful. With the leading players in their respective fields. That’s a sober initial decision to take: market leaders have to address each other as equals.” A meeting of Sun Kings, then? Not a chance: “Finstral has remained very much down to earth, always very close to its material, something we very much liked right from the start,” says Didier. “We believe in the saying: business is what matters. And that is how Finstral operates. That’s why we first talk to Finstral if we want to know if an idea is any good or not. Without Finstral, we would not be able to bring Saint-Gobain’s window-visions to market.” Florian Oberrauch adds: “Your innovations drive Finstral forwards. And maybe ours help push Saint-Gobain onwards too.”

Because we want to know what will happen when the self-styled window and glass nerds put each other under so much positive pressure. What will be next mass production idea that does not mean that the glass breaks into a hundred thousand pieces one thousand times in a row? Fabrice Didier, with a doctorate in solid-state physics, first has to step back a little. “When I learned that glass is in physical terms a fluid... fluid, but with infinite viscosity, I was fascinated. Glass is ancient, more than 7,000 years old, humankind’s oldest artificially produced material, yet at the same time one of the most modern. And in the window, on the boundary between inside and outside, this material has to perform an enormous number of different tasks in our time.” Didier lists them while Florian Oberrauch nods and adds to them: - Control of energy transmissibility! Heat should remain inside in winter and outside in summer. “We’re working on smart windows that will adjust automatically,” says Didier. “In five years they will be ready,” is Florian’s estimate. “We’re already testing them at our head office in Unterinn, and soon we’ll be introducing them in Gochsheim too.” He looks at the ceiling: “Then maybe we won’t need the ventilation any more.” Saint-Gobain incidentally is already working on a heating glass that will itself generate radiant heat. - Ease of cleaning! “Don’t underestimate this,” says Fabrice Didier. “The bigger the window panes, the harder they are to clean. We continue researching into so-called self-cleaning glass.” Saint-Gobain already offers types of glass with a coating that makes it easy for a rain shower to rinse dirt off the window. - Security! Protection against break-ins, accidents, noise or unwanted attention. - Lightness! “We want it to be possible to install our insulation glass without using a crane,” explains Didier. “So the aim is to make double glazing that has the insulating properties of triple glazing, but weighs less.” When in 2008 Saint-Gobain first presented its flat glass with an unbelievable Ug value of 1.0, one of its competitors said in resignation: “The Olympics are over now.” Didier immediately countered, “There’s is no end to the story. Research and development know no limits with glass.” Infinite stories can be made of glass.

Because we want to know what will happen when the self-styled window and glass nerds put each other under so much positive pressure. What will be next mass production idea that does not mean that the glass breaks into a hundred thousand pieces one thousand times in a row? Fabrice Didier, with a doctorate in solid-state physics, first has to step back a little. “When I learned that glass is in physical terms a fluid... fluid, but with infinite viscosity, I was fascinated. Glass is ancient, more than 7,000 years old, humankind’s oldest artificially produced material, yet at the same time one of the most modern. And in the window, on the boundary between inside and outside, this material has to perform an enormous number of different tasks in our time.” Didier lists them while Florian Oberrauch nods and adds to them: - Control of energy transmissibility! Heat should remain inside in winter and outside in summer. “We’re working on smart windows that will adjust automatically,” says Didier. “In five years they will be ready,” is Florian’s estimate. “We’re already testing them at our head office in Unterinn, and soon we’ll be introducing them in Gochsheim too.” He looks at the ceiling: “Then maybe we won’t need the ventilation any more.” Saint-Gobain incidentally is already working on a heating glass that will itself generate radiant heat. - Ease of cleaning! “Don’t underestimate this,” says Fabrice Didier. “The bigger the window panes, the harder they are to clean. We continue researching into so-called self-cleaning glass.” Saint-Gobain already offers types of glass with a coating that makes it easy for a rain shower to rinse dirt off the window. - Security! Protection against break-ins, accidents, noise or unwanted attention. - Lightness! “We want it to be possible to install our insulation glass without using a crane,” explains Didier. “So the aim is to make double glazing that has the insulating properties of triple glazing, but weighs less.” When in 2008 Saint-Gobain first presented its flat glass with an unbelievable Ug value of 1.0, one of its competitors said in resignation: “The Olympics are over now.” Didier immediately countered, “There’s is no end to the story. Research and development know no limits with glass.” Infinite stories can be made of glass.

Lively exchanges between equals: between Saint-Gobain glass and Finstral windows.

Glass factory with glass façade: Finstral has a state-of-the-art production plant for insulation glass in Gochsheim in Lower Franconia – and presents its product range in Finstral Studio.

Gochsheim host: André Mehlhorn, board member, Finstral Deutschland, shows Fabrice Didier (centre) and Florian Oberrauch through the new insulation glass production hall.

Large-scale: the 6 x 3.21-metre standard glass panes from the Saint-Gobain plants are delivered to Gochsheim on special carriers, where they are prepared for cutting by a giant robot.

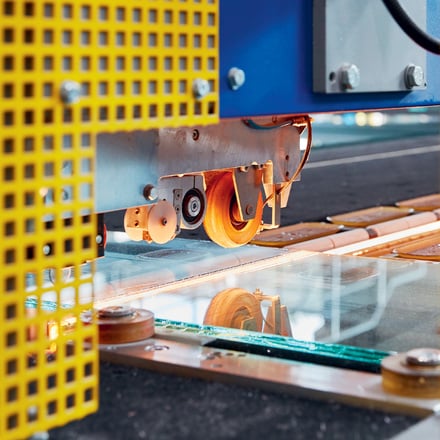

Accurate to the millimetre: the laminated glass for each Finstral window is individually cut under computer control, optimised to minimise waste.

Perhaps the question of the impulse behind it is simply: why all this, why such a passion for glass for windows and windows for glass? “We need and make windows,” replies Fabrice Didier, “because people need natural light. Without light we would suffer a nervous collapse. A child’s brain needs at least 300 lux for at least three hours a day in order to develop. There is no life without light.” Many architects know this, of course, and their desire to create stories using as much glass as possible remains unbroken. And Didier is sure that Finstral, more than other window manufacturers, has a special sense for light. “The frame plays an important role. But the profiles are narrow, so the glass is at least as crucial. Finstral recounts a great deal using glass and light, more than other window manufacturers.” Fabrice Didier, top manager in a global corporation with nearly 180,000 employees and many products other than glass, speaks this phrase – one that seems to come from his deepest soul. While he states this about the Oberrauchs and Finstral, it is at least just as much about himself: “Market leadership is good, innovation is great. But loving and living glass is the finest of all.”

It all began for Saint-Gobain with mirror glass for the Palace of Versailles: today, the French group is Europe’s leading flat glass manufacturer and number two in the world – with more than 34,000 employees in 34 countries in this sector alone. Since 2015 Finstral has been using only Saint-Gobain glass. The image shows cut-to-size insulation glass panes on transport trolleys – ready for assembly.

Still want more?

See here for further interesting reading matter.