Questions of space.

Reflected surroundings. José Pedro Croft’s sculptures seek a dialogue with architecture.

Text: Gesine Borcherdt

If we define space as a limit that provides a frame, then ultimately everything is space. And everything is finite. All that surrounds us. Life. Ourselves. Wow, that’s all pretty existential! And that is precisely the intention of Portuguese artist José Pedro Croft. He overturns and reflects our surroundings, opening and activating them. And thus questions our existence.

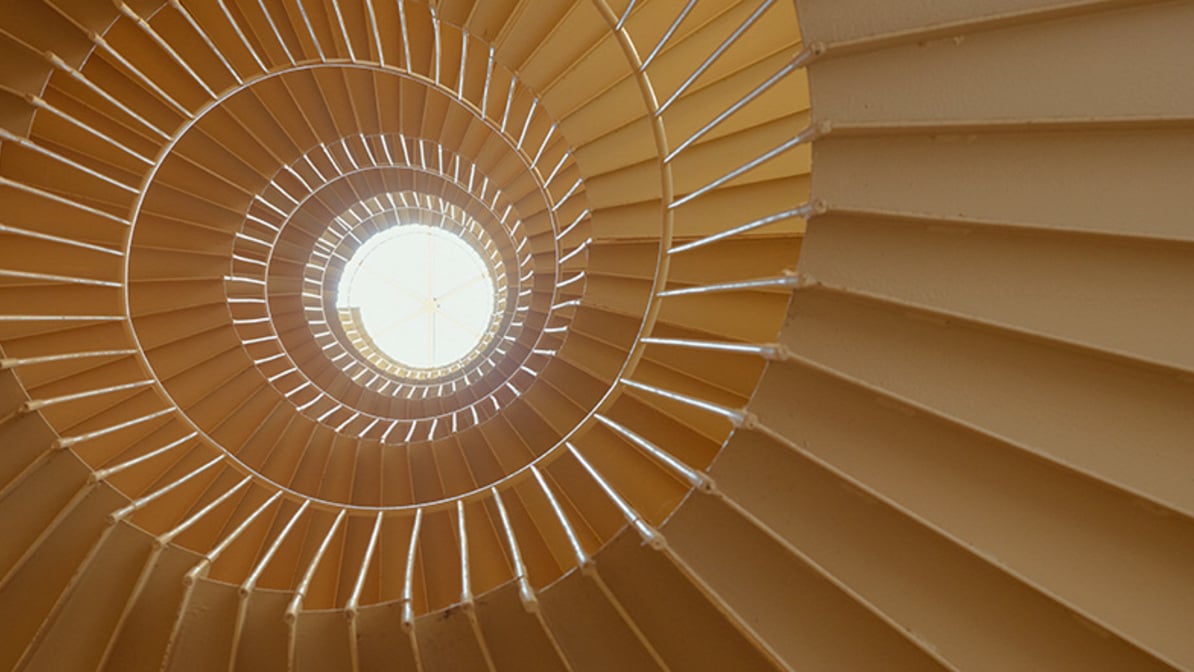

Even as a child, José Pedro Croft knew that he would become an artist. That was in the 1960s, when Portugal was a poor, rural country: if it had fallen into the sea off the westernmost edge of Europe, few would probably have noticed. But then there is Porto, a picturesque, somewhat dilapidated port on the Atlantic. It is currently experiencing a wave of clear, fleet-footed architecture that is transforming the city into an amazing setting for modern building techniques. All thanks to Álvaro Siza. In 1958, one year after José Pedro Croft was born in the city, Siza opened his architectural firm there and began to teach at the university. He placed a series of minimalist buildings in the landscape that merge with their surroundings in an almost magical way: a tea house crouches like a flat rock on a rocky coast, social housing is elegantly lined up like beach houses, while offices, banks and hotels acquire a floating aspect. Siza’s influence makes waves. Being an architect in Porto is more than just a profession – it is a mandate to make people look at their surroundings.

It is this world that José Pedro Croft has witnessed since childhood, as his four uncles were architects. “I often spent time in their offices, saw their drawings and models. That really impressed me,” he says. “Architecture was for me a part of the fine arts. I knew right away that I wanted to devote all of my time and energy to the subject of space – but as an artist, not as an architect.”

José Pedro Croft’s family soon moved to Lisbon; he brought with him his desire to become an artist. He still lives there today, where for over 40 years now he has been making sculptures and drawings that have just one subject: the exploration of space. Yet it would be wrong to believe that the DNA of the architect Álvaro Siza and Croft’s architect uncles is solely concentrated there. “I look at the world as a whole. Art, cinema and poetry move me just as greatly as landscape and architecture. Ancient Egypt is very important for me. The way in which space was addressed was like conceptual art – a matter for the mind.” Greek sculpture is also a source of fascination for him as this represents a perfectionist attempt to depict the body and its movement in space, for instance in the case of the famous Laocoon group. Or the Russian Constructivists, who explored space through geometric abstraction. And of course Brâncuşi and Giacometti... “My list is endless. The relationship between body and space is, finally, elementary in art.”

If so, wasn’t the topic settled long ago? Especially if, like José Pedro Croft in the 1980s, you begin with art – at a time when American minimalists had already, with their steel boxes, copper plates and neon tubes, pushed the questioning of space to extremes. “The questions of form, material and their effects in space have never been answered,” says Croft. “So you have to keep going. Sculpture today raises the same problems as it did in prehistory. Would Richard Serra have erected his steel walls if ancient stone monuments had already determined the relationship between positive and negative space, fullness and emptiness?”

José Pedro Croft does not at any rate work much with such bulky materials. His frugal sculptures are made of metal frames, often combined with coloured glass. They appear stable, but also light, almost dancing. They activate the space that surrounds them, that they enclose and at the same time let pass and reflect. Glass is for him a fascination. “It marks boundaries, yet you can still see through it. The boundaries are emphasised by the metal frame, as with a window.” And glass too is a mirror: the observer sees him or herself and at the same time what is happening behind the glass. “The glass becomes a moving picture. This is paradoxical within a sculpture.”

“The glass becomes a moving image. Within a sculpture this is paradoxical.”José Pedro Croft

If we define space as a limit that provides a frame, then ultimately everything is space. And everything is finite. All that surrounds us. Life. Ourselves. Wow, that’s all pretty existential! And that is precisely the intention of Portuguese artist José Pedro Croft. He overturns and reflects our surroundings, opening and activating them. And thus questions our existence.

Even as a child, José Pedro Croft knew that he would become an artist. That was in the 1960s, when Portugal was a poor, rural country: if it had fallen into the sea off the westernmost edge of Europe, few would probably have noticed. But then there is Porto, a picturesque, somewhat dilapidated port on the Atlantic. It is currently experiencing a wave of clear, fleet-footed architecture that is transforming the city into an amazing setting for modern building techniques. All thanks to Álvaro Siza. In 1958, one year after José Pedro Croft was born in the city, Siza opened his architectural firm there and began to teach at the university. He placed a series of minimalist buildings in the landscape that merge with their surroundings in an almost magical way: a tea house crouches like a flat rock on a rocky coast, social housing is elegantly lined up like beach houses, while offices, banks and hotels acquire a floating aspect. Siza’s influence makes waves. Being an architect in Porto is more than just a profession – it is a mandate to make people look at their surroundings.

It is this world that José Pedro Croft has witnessed since childhood, as his four uncles were architects. “I often spent time in their offices, saw their drawings and models. That really impressed me,” he says. “Architecture was for me a part of the fine arts. I knew right away that I wanted to devote all of my time and energy to the subject of space – but as an artist, not as an architect.”

José Pedro Croft’s family soon moved to Lisbon; he brought with him his desire to become an artist. He still lives there today, where for over 40 years now he has been making sculptures and drawings that have just one subject: the exploration of space. Yet it would be wrong to believe that the DNA of the architect Álvaro Siza and Croft’s architect uncles is solely concentrated there. “I look at the world as a whole. Art, cinema and poetry move me just as greatly as landscape and architecture. Ancient Egypt is very important for me. The way in which space was addressed was like conceptual art – a matter for the mind.” Greek sculpture is also a source of fascination for him as this represents a perfectionist attempt to depict the body and its movement in space, for instance in the case of the famous Laocoon group. Or the Russian Constructivists, who explored space through geometric abstraction. And of course Brâncuşi and Giacometti... “My list is endless. The relationship between body and space is, finally, elementary in art.”

If so, wasn’t the topic settled long ago? Especially if, like José Pedro Croft in the 1980s, you begin with art – at a time when American minimalists had already, with their steel boxes, copper plates and neon tubes, pushed the questioning of space to extremes. “The questions of form, material and their effects in space have never been answered,” says Croft. “So you have to keep going. Sculpture today raises the same problems as it did in prehistory. Would Richard Serra have erected his steel walls if ancient stone monuments had already determined the relationship between positive and negative space, fullness and emptiness?”

José Pedro Croft does not at any rate work much with such bulky materials. His frugal sculptures are made of metal frames, often combined with coloured glass. They appear stable, but also light, almost dancing. They activate the space that surrounds them, that they enclose and at the same time let pass and reflect. Glass is for him a fascination. “It marks boundaries, yet you can still see through it. The boundaries are emphasised by the metal frame, as with a window.” And glass too is a mirror: the observer sees him or herself and at the same time what is happening behind the glass. “The glass becomes a moving picture. This is paradoxical within a sculpture.”

“The glass becomes a moving image. Within a sculpture this is paradoxical.”José Pedro Croft

With his large-format sculptures, José Pedro Croft (born in 1957) seeks a dialogue with architecture.

Reflected reality: the commissioned work standing in front of the Finstral Studio in Friedberg near Augsburg is a variation of the six-part installation “Uncertain Measure” of steel and coloured glass that José Pedro Croft originally developed for the 2017 Biennale of Venice.

Glass as image has a turbulent history in art. Anyone who has seen how sunlight penetrates through stained-glass windows knows that coloured glass can not only itself come to life, but can also almost magically transform a room. Reflections play no part here – it is rather a matter of the mystical, emotional moment, as when a church lights up like a higher being.

When José Pedro Croft represented Portugal at the Venice Biennale in 2017 and exhibited a series of sculptures in a garden on the Giudecca, the tradition of glass-making, the numerous churches and the shimmering waters around Venice all formed an integral part of his work. But the dialogue with the surroundings went even further. His installation “Uncertain Measure” – monumental windows of red and blue glass, tilted and enclosed like sails in heavy steel frames – was set up in the immediate vicinity of a never-completed housing project. It was designed in the early 1980s by none other than: Álvaro Siza. For Croft, this closed a circle. “My sculptures reflected the structure of Siza’s unfinished buildings. They carried their matrix within them – like memorabilia.”

It is true that José Pedro Croft’s designs always have something of a melancholy ambivalence, strangely fragile and powerful at the same time. That is why they have something of the living in them. In spite of their reduction, they are metaphors for the human body and the human being, standing for this contradictory mixture of strength and fragility. Practically no other material apart from glass – in which we are reflected, which opens our eyes and yet possesses its own unique identity – could express this so aptly. “Art always deals with the question of life and death,” says Croft. “We never stop thinking about this. Why are we here, and for how long? What will come after us?” There is no answer. But there is a way to get around these questions – with art, which is for José Pedro Croft much more than what we see.

When José Pedro Croft represented Portugal at the Venice Biennale in 2017 and exhibited a series of sculptures in a garden on the Giudecca, the tradition of glass-making, the numerous churches and the shimmering waters around Venice all formed an integral part of his work. But the dialogue with the surroundings went even further. His installation “Uncertain Measure” – monumental windows of red and blue glass, tilted and enclosed like sails in heavy steel frames – was set up in the immediate vicinity of a never-completed housing project. It was designed in the early 1980s by none other than: Álvaro Siza. For Croft, this closed a circle. “My sculptures reflected the structure of Siza’s unfinished buildings. They carried their matrix within them – like memorabilia.”

It is true that José Pedro Croft’s designs always have something of a melancholy ambivalence, strangely fragile and powerful at the same time. That is why they have something of the living in them. In spite of their reduction, they are metaphors for the human body and the human being, standing for this contradictory mixture of strength and fragility. Practically no other material apart from glass – in which we are reflected, which opens our eyes and yet possesses its own unique identity – could express this so aptly. “Art always deals with the question of life and death,” says Croft. “We never stop thinking about this. Why are we here, and for how long? What will come after us?” There is no answer. But there is a way to get around these questions – with art, which is for José Pedro Croft much more than what we see.

Tilted perception: the four-part installation in the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (Untitled, 2003) frames outward and inward views.

Glass, vinyl and mirror surfaces become a spatial structure and at the same time intervene in the structure of the surrounding environment (Untitled, 2011).

Still want more?

See here for further interesting reading matter.